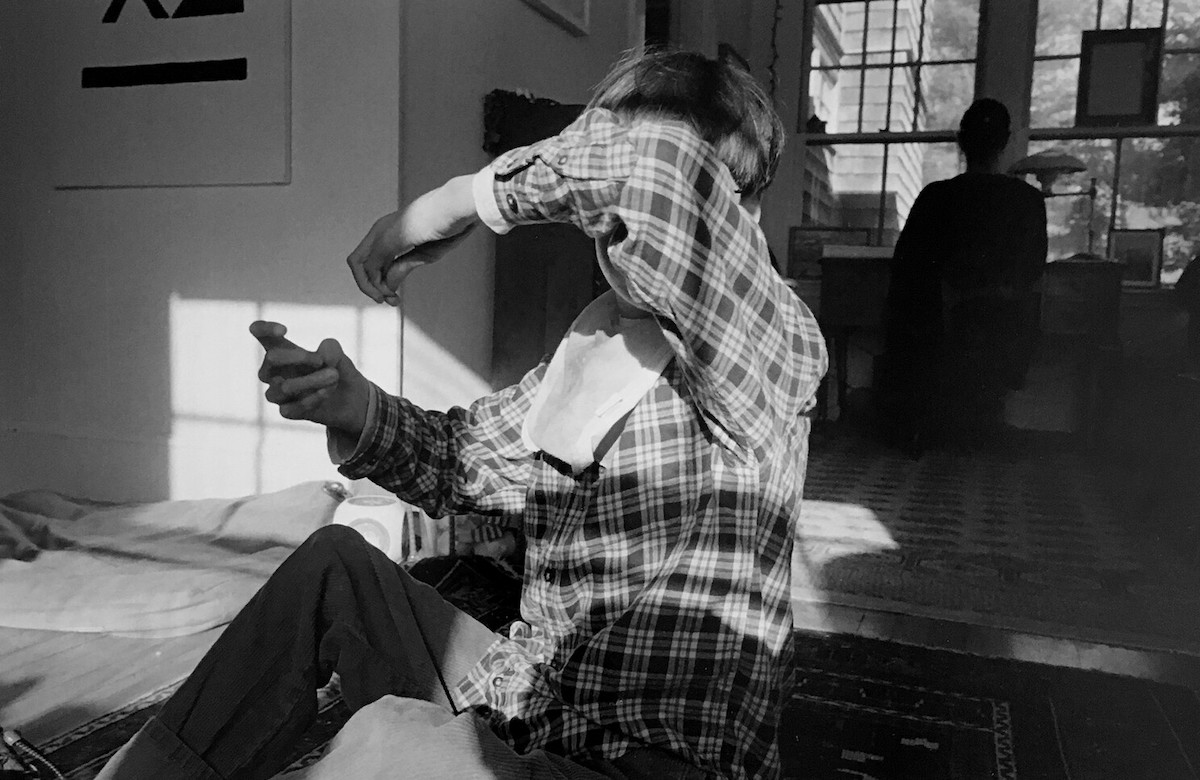

Calvin

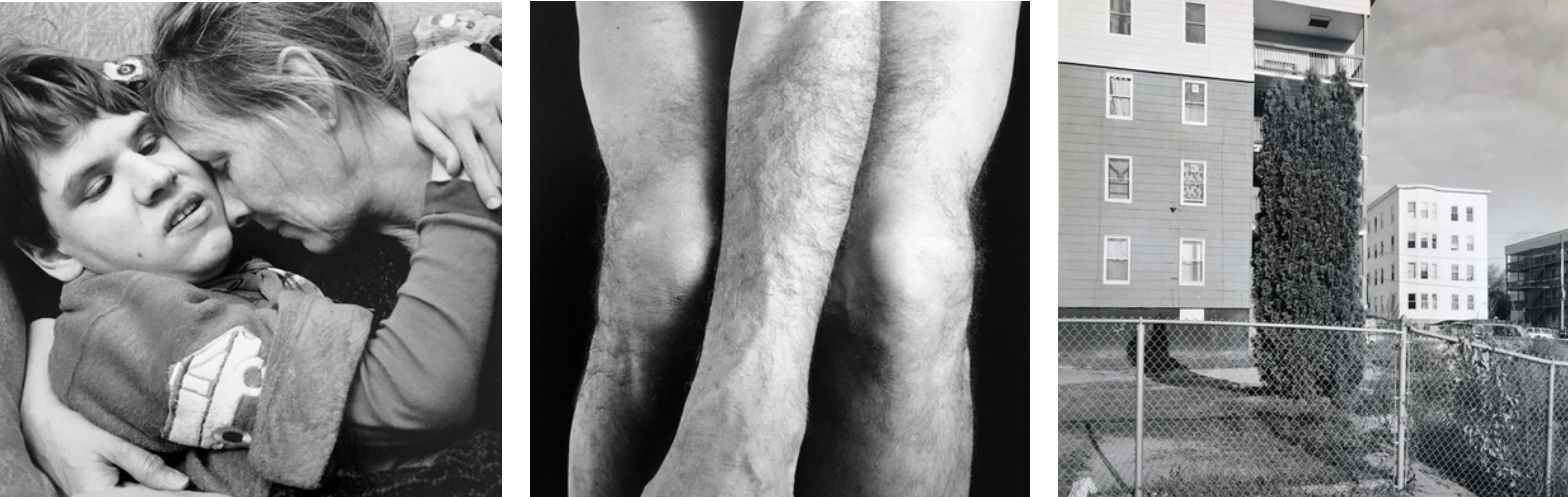

Sunlight fractures the room’s clean geometry as shadows loom. Arms are tossed, fingers gnarled, the boy’s face obscured, his raised elbow appearing to fend off the world. In the background, a silhouette (his mom).

In rippling black and white, it is an enigmatic image, as startling as it is beautiful.

“I’ve been photographing Calvin since he was born, but in different amounts of intensity,” says Michael Kolster, a Maine-based photographer and Calvin’s father. “I started photographing him in this last cycle when he turned 16. I started seeing him change very quickly from a younger person taking on physical characteristics that didn’t make him a child anymore. How did that feel? What did it mean?”

In 2004, Calvin was born with significant neurological disabilities that left him unable to communicate and subject to chronic seizures: he will never be able to dress, feed, bathe, or take care of himself. Calvin is as fully dependent on his parents as he is incapable of conveying to them who he is: how he dreams, what he fears, if he loves.

For Michael, it is a physical and emotional challenge to photograph his son.

“He won’t hold still, he can’t communicate, I can’t talk to him. He is completely unaffected by my need to take photos of him. I’m not even sure I’m making pictures of him because he doesn’t know what’s going on.”

Eschewing heartstring-pulling stereotypical images that risk proffering false notions of what it means to inhabit a world of profound disability, Michael avoids any pretense of knowing anything about Calvin’s inner reality in his photographs. As well he should, for what could be less congruent with a father’s love for his unfathomable son than pat answers to impossible questions?

“Flirting with cliches around a child with disabilities was my biggest fear about those pictures,” says Michael.

In place of trope’s false comfort, Michael delivers unyielding impenetrability as the essence of Calvin’s Calvin-ness, and the defining quality of his relationship with his son.

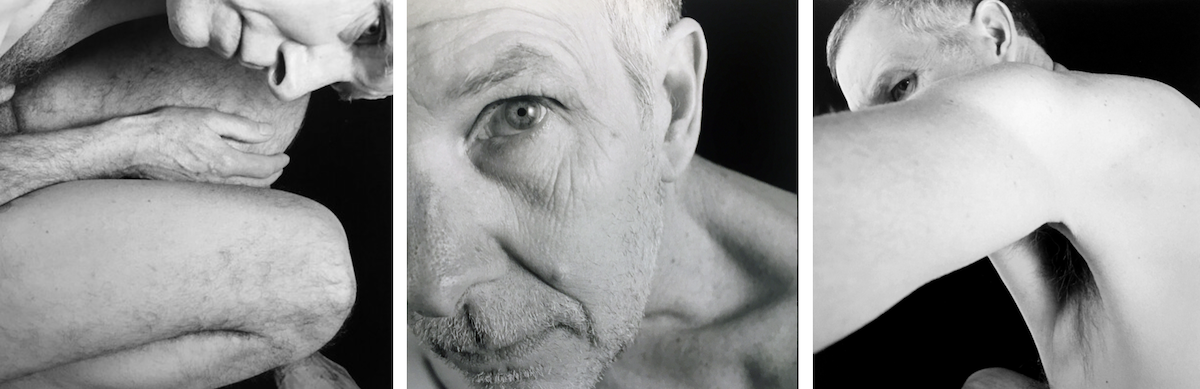

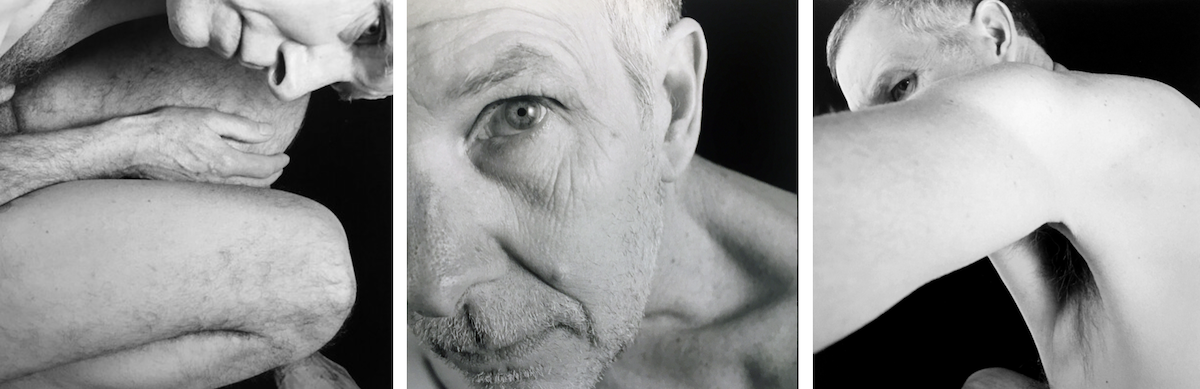

Michael

The body is aged and naked. They are self-portraits, feral and beautiful, and Michael felt compelled to take them.

“I was thinking about consent, especially with Calvin, and how if I was going to take pictures of him and Christy [his wife], expose them in that way, then it was only fair I do that with myself too.”

And so he does.

Bare, Michael appears neither comfortable nor uncomfortable. He is simply there, as if by accident, like a wild thing randomly caught by a trail camera.

Impenetrable and raw (like Calvin).

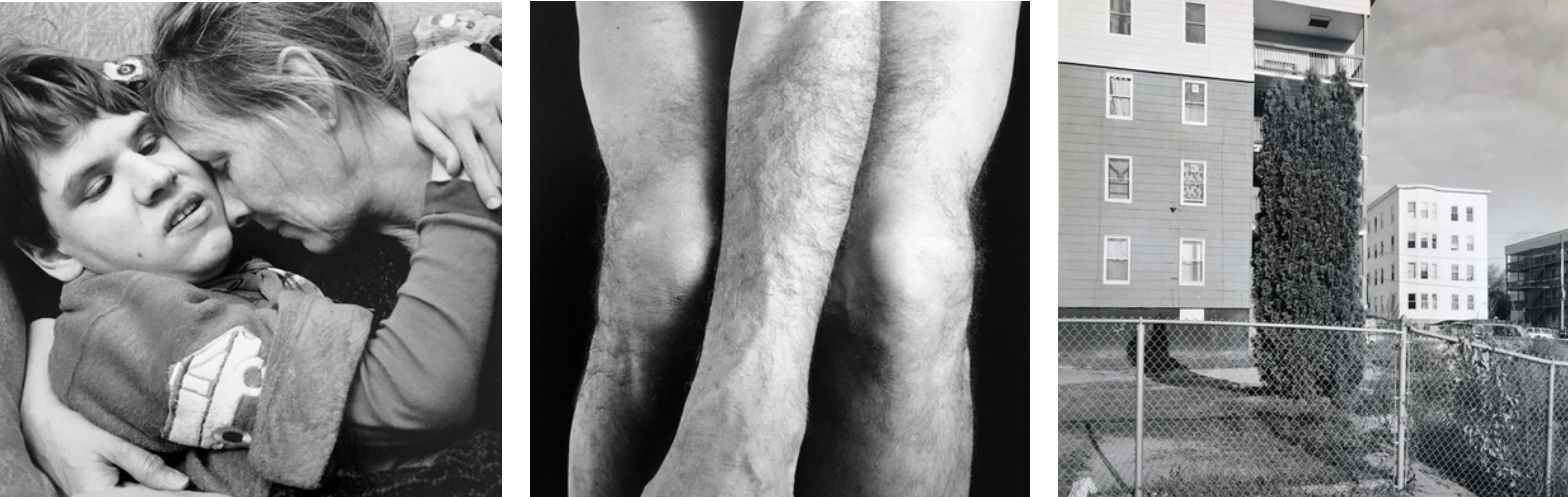

Lewiston

Michael thinks of his street scenes from Lewiston, Maine, as among his most intimate work – more so than his photos of Calvin or self-portraits. In making them, there is nothing between him and what he chooses to look upon: the landscape is a cooperative subject (unlike Calvin), and Michael has complete agency on where he points his camera (unlike with his self-portraits). Intimacy resides not in the subject matter so much as in the unbroken connection between the viewer and what he views: the world Michael presents is fully of his own making.

He has control, and accordingly can shape outcomes.

“The choices are much more revealing of what I think and what I care about than maybe any of the others,” he says.

And what is that exactly?

Consider this photograph:

It seems at first glance a simple visual dialogue between two contrasting worlds: the “natural” (the tree-scape) with the “artificial” (the mural). An uncomplicated, even trite, conceit. But then there is the parking sign peeking up along the bottom left. Next we might notice the wedge of roofline poking up to the right of the sign, a distraction from the otherwise clean line between the natural tree-scape and painted wall. These visual interlopers appear like photobombs, undermining a superficial first take.

In refusing cliche (again), Michael’s choices challenge our snap judgment, inviting us to linger longer. Doing so, we discover (and then luxuriate in) visual wonder: the dance of light and dark patterned across the silver gelatin surface; the symphonic play of diagonal lines, long and thick, short and rapid (leaf ridges, pine needles, branch stems and tree limbs all in play); the pop of that parking sign, then pine cone and bird, each startling as an Easter egg; the image’s bifurcation, stranger and stranger the longer we look.

In his Lewiston series, Michael gives no harbor to easy explanation – only enchantment.

His is a vision as enrapturing as it is inscrutable.

HOME and Other Realms

The child, Michael’s son, Calvin. The body, Michael’s own. The place, Lewiston, Maine’s second largest city, frequented by the photographer for decades.

Each series has its own separate subject. Ostensibly, they do not belong together.

And yet recently at the University of New England, Michael presented HOME and Other Realms, an exhibition combining these three series, testing any presumption of unrelated-ness between the works.

“I wanted to see what happens when you put the three modes together and give them equal weight,” he says. “Doing so begs the question, why put them together?”

It is no whim; Michael is too intentional a photographer for that. He installs his show like a five-paragraph essay: an introductory section combining works from all three series; followed by a trio of sections, one on each series; then a concluding section that restates the structure of the opening: thesis, support, support, support, thesis.

Michael’s installation design is making an argument, and with it (just as with his parking sign among the foliage) he is asking us to pay attention.

But to what?

******

I have spent weeks wrestling with writing about Michael’s work, re-writing this closing section dozens of times, never to my satisfaction. I have tried, and cannot bring it to a tidy conclusion.

I have not been able to adequately answer the question: “But to what?”

Certain threads of possibility seem stronger than others – the recurring theme of impenetrability for example.

In his artist’s statement accompanying HOME and Other Realms, Michael writes of Calvin, “I am struck by how hard it is to forge a bond with him, either spiritually or emotionally. Camera in hand, I feel apart.”

So perhaps not impenetrability then, but apartness (certainly an abiding reality for Michael, particularly in relationship to his Calvin). But my every attempt at tying meaning into a bow unravels, each effort at summation collapsing from the weight of over-sentimentalization or inadequacy.

Clean conclusions do not adhere, and elucidation is evasive. There always remains an unyielding hidden layer.

Which brings us back to Calvin, whose photograph we began with, and whose own confounding elusiveness I see echoing in the riddle at the core of Michael’s artistic choices: ultimately, both defy comprehension.

They simply are.

Like love.

Which, in the end, may be the entire point.