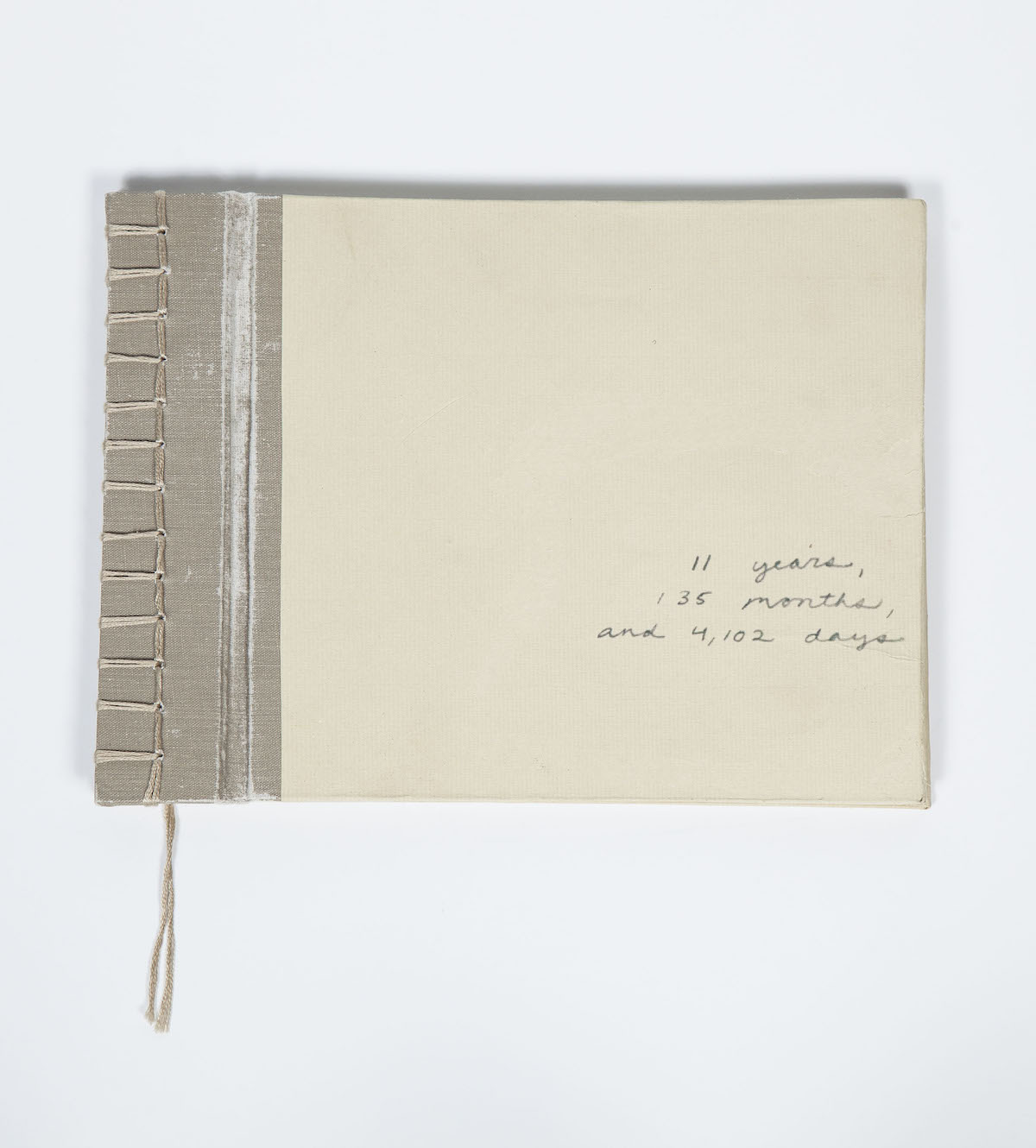

Prologue

Studio

“I don’t think about art when I’m working. I try to think about life.”

—Jean-Michel Basquiat

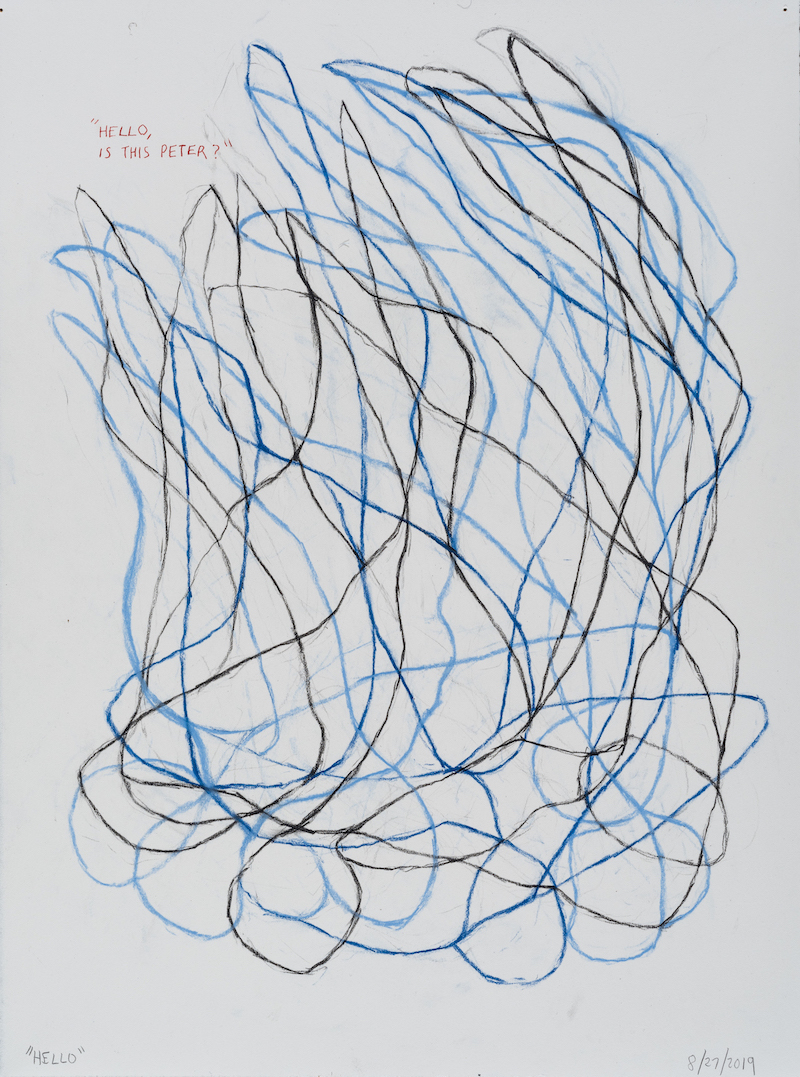

For the past couple months, I’ve had the pleasure of working in one of the best studios I’ve ever had: spacious, light-filled, plenty of walls. Formerly a two-car garage, it’s now where I make my art.

When painting, I always listen to music, flipping between Spotify and my vinyl records from college. Anything from Mozart to the Clash—whatever suits my mood. I play loud, for there’s nobody around to be disturbed—I live surrounded by woods.

The music clears my head from thinking too much about making art.

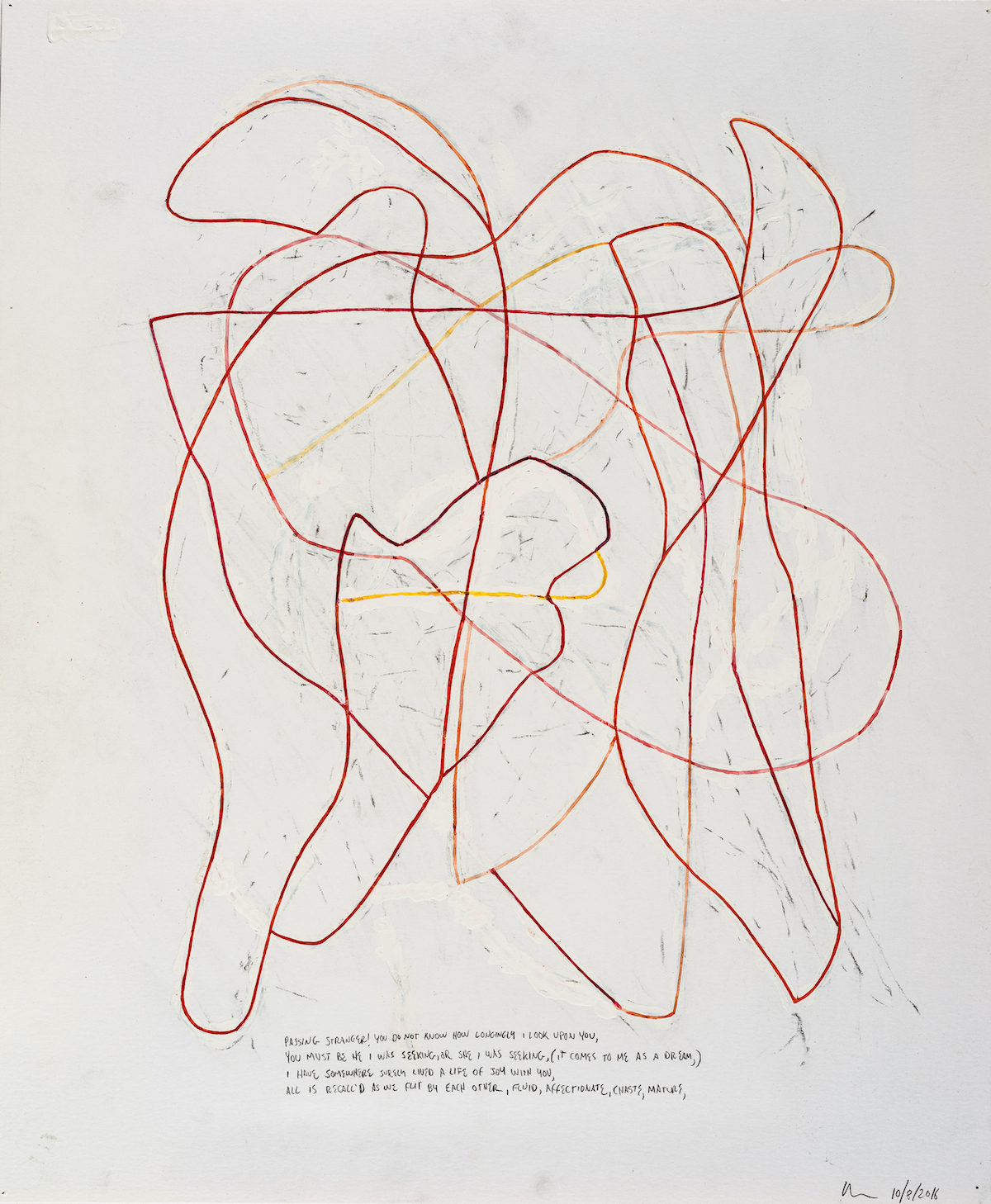

French painter Georges Braque once said, “It is the act of painting, not the finished painting” that matters. Jean-Michel Basquiat, quoted above, had the same approach, and it’s mine as well: I go to my studio more to breathe and be than produce.

I get to breathe every day.

How lucky I am.

Tuesday was Election Day. I drove to my town’s polling station, cast my vote, and at the exit passed a gauntlet of folks seeking signatures in support of various causes. I spoke with each, signing their petitions. One person was collecting signatures to gather a show of support from residents ahead of her organization (Healthy Kids) going before town officials to seek a supplemental grant. With a mission “to encourage, support and promote healthy families” and “to prevent child abuse and neglect,” Healthy Kids needed a relatively small amount to build better online resources to serve local families (Covid continues to present challenges).

Having once run a non-profit myself, I felt a flare of empathetic frustration, thinking of these hardworking folks trying to do right by young people in my new hometown ensnared by local government bureaucracy. Because at that moment I knew I could help, I decided I would. I made what was for me a large financial contribution as soon as I got home.

I felt like a citizen.

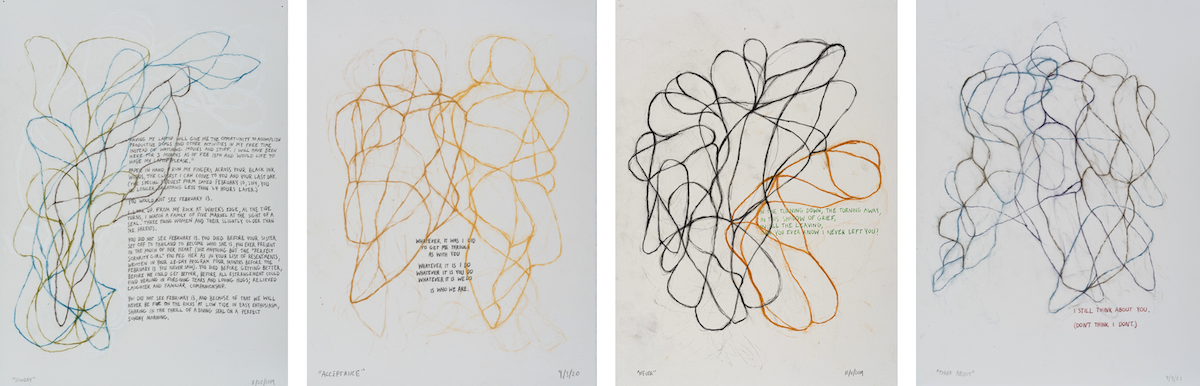

Holding and releasing. Living inward and looking outward. Taking care of myself and tending to others—these are poles I navigate.

There is so much hardship. So much for us to carry—to rise from—to do for ourselves as well as for others. I oscillate (side to side, up and down) across that sweet spot of repose between self and community. Balance seems a chimera; arrival fleeting.

In trying to figure out the harmony of it all, I know I am not alone.

In a few days, I will be part of a program presented by Reimagine called Phoenix Rising: Models of Grief, Growth, and Action. My friends Ashley Minner (who I write about below) and Kondwani Fidel will join me online, and we’ll talk with our audience too about their own lives and situations. One of the things I hope to share during the event is all I get from being in the studio. How out of that process I somehow find healing, land on gratitude, shape my intentions for how to be in this world—and how actions follow.

To share how in all my studio’s imperfect vibration—in my music and thought—I am forever learning the art of living.

Of being and giving.

—Peter