Prologue

All of Her

The wrong things are kept secret, and it destroys people.

– Nan Goldin

Last Saturday, I went to see All the Beauty and the Bloodshed at my hometown movie theater.

The film traces the life of photographer Nan Goldin, who spent years campaigning to remove the Sackler family name from museum walls, given their central role as instigators of the opioid epidemic (my daughter one of its victims).

Goldin became addicted to OxyContin after being prescribed it. She survived an overdose, and later learned the Sacklers became fabulously wealthy from OxyContin sales and had been cleansing their name through museum philanthropy. She was infuriated.

Her campaign succeeded: for once, truth won, and the Sackler name came tumbling down.

Goldin knew that silence is deadly.

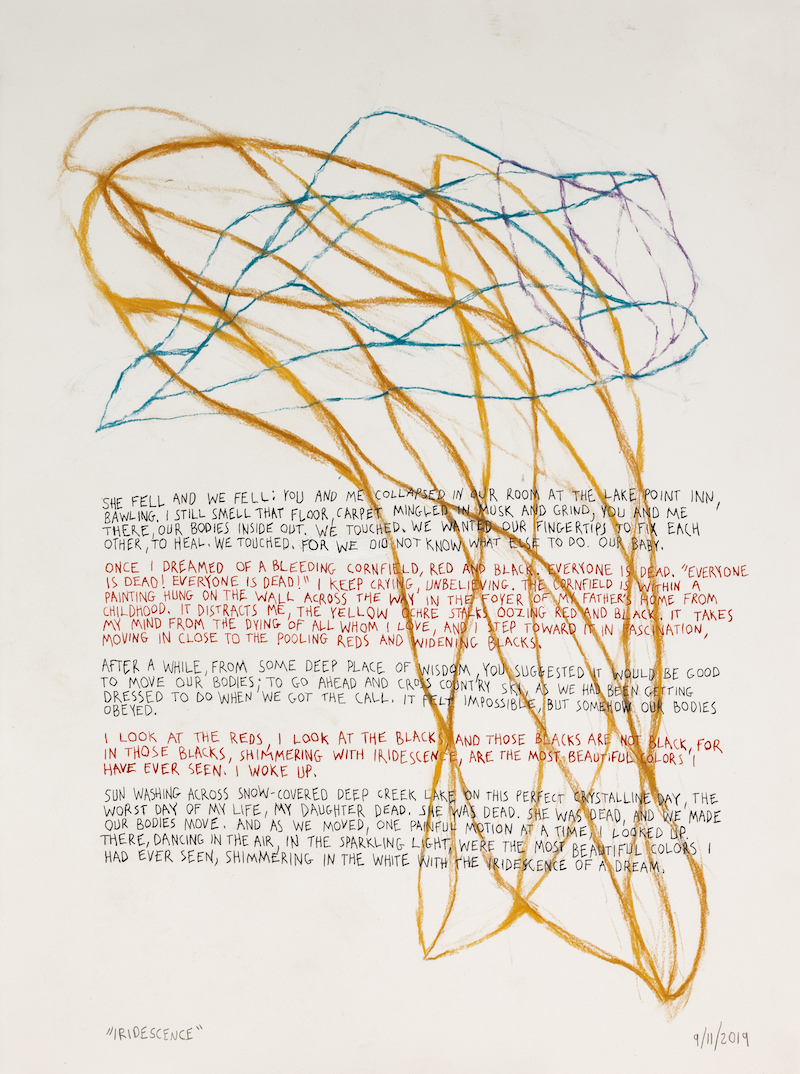

Today (February 11) is the ninth anniversary of Elisif’s fatal overdose. Her opioid addiction began with OxyContin, but her death is not entirely the Sackler family’s fault. In our erring, our silence, our avoidance, we all have a modicum of complicity in the ravages of the opioid epidemic: it is our epidemic.

That’s a hard truth to accept, but as Goldin’s crusade demonstrates, secrets and lies kill.

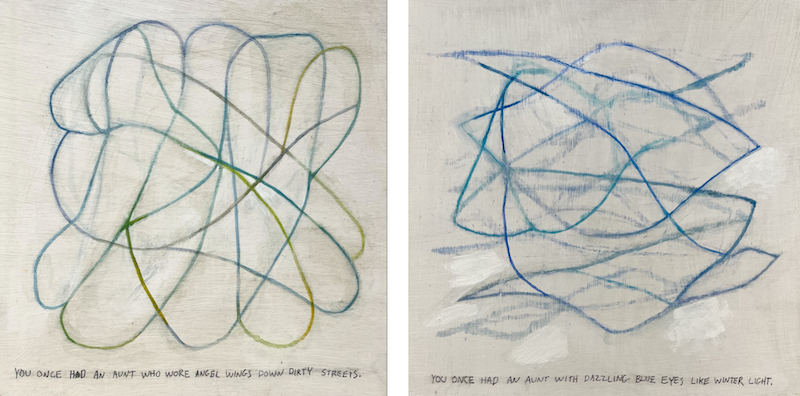

I abhor the idea of keeping secrets about Elisif. To censor her story is to hide the truth, bowing to shame and stigma, perpetuating harm.

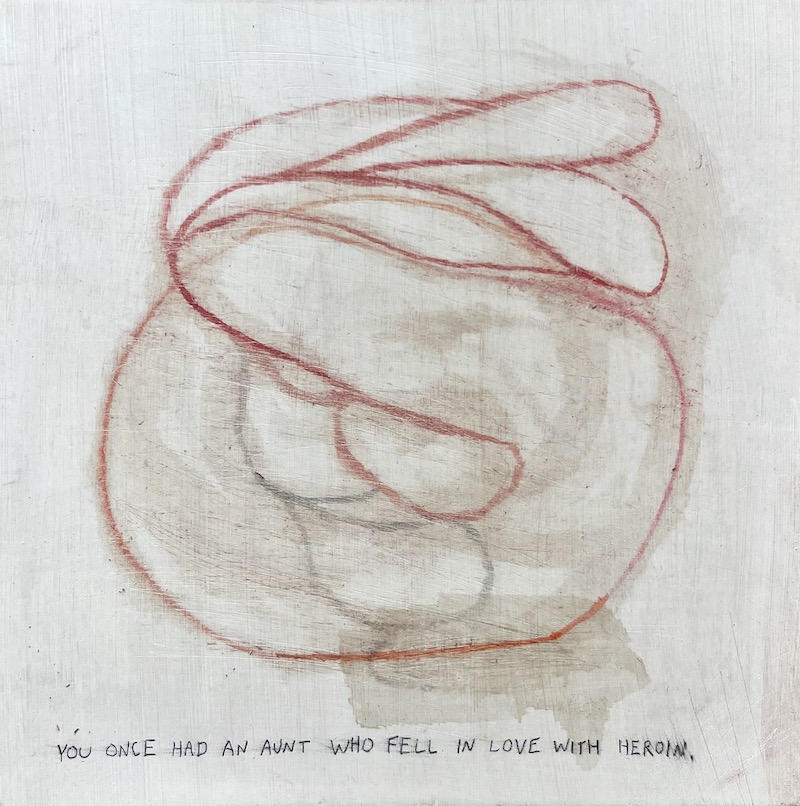

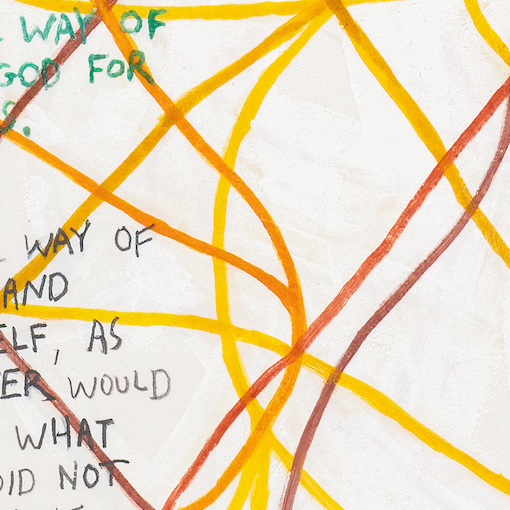

In a new series of paintings, I’ve been thinking about my soon-to-be-grandchild and the aunt he’ll never meet. I want him to know her – all of her.

August 31 is International Overdose Awareness Day, a day to remember those who have died, and honor the grief of surviving family and friends. Before moving to Maine in 2019, I took part in events every August 31 in Baltimore, as a presenter, audience member, and program organizer. We would share stories. We would light candles. We would remember, together.

It was always beautiful.

In Lincoln County, the rural county where I now live, people are dying. I’m glad to be partnering with a growing team of organizations and individuals to plan events this August 31 honoring those we’ve lost. In sharing their stories, we’re shattering the culture of secrecy that has destroyed so many.

On that day, standing in the light of truth, breaking the silence, we will remember, together.

– Peter Bruun