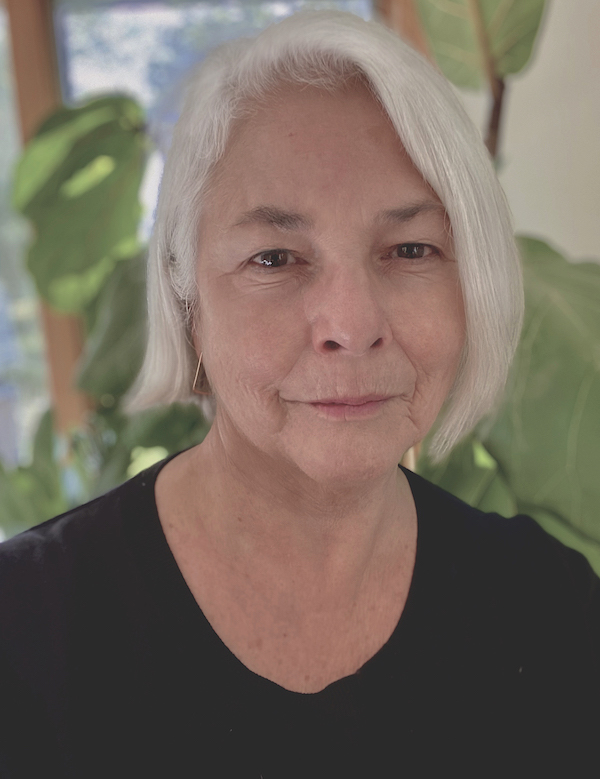

Kate Beck is a quintessentially Maine painter, though it’s only with her recent Will’s Strait series that we see it clearly.

Being a “Maine painter” does not mean any one thing, but certain tropes come to mind. Artists such as Winslow Homer, Andrew Wyeth, and Marsden Hartley long ago established a kind of blueprint for what to expect: rocky coasts, picturesque boats, rugged lobstermen. Such imagery (so emblematic of Maine) populates galleries throughout the state.

Of course, plenty of Maine artists make and exhibit art far different from this type. But while their work is made in Maine, its content is generally not seen as of Maine. For the Maine painter, there is little escape from proximity to pine trees and sailboats, wood-handled axes and fishing nets.

Such imagery is largely absent from Kate’s oeuvre; she does not consider herself to be a representational painter.

“I make abstract art,” she says.

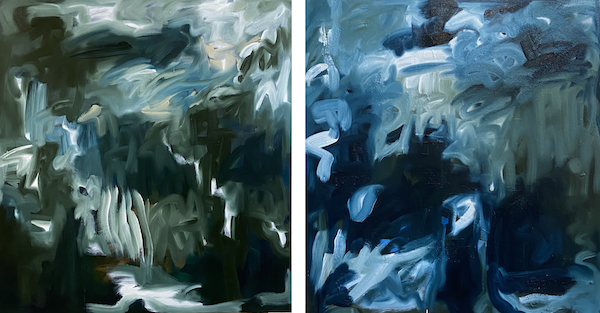

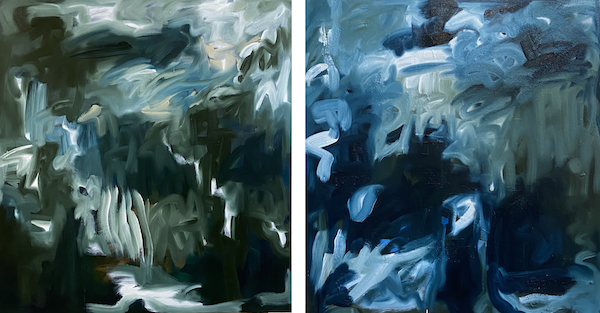

And she does so beautifully and subtly. To be with her paintings is to be in the presence of wonder and nuance. As we look, what might initially appear to be a work randomly covered in brushstrokes reveals itself over time to be a composition with a deceptively lush range of marks and underlying architecture: there is structure to these works. This becomes clear as our eye moves across the surface, guided by well-placed shade and color from corner to corner, our gaze drawn into continuous visual meander. The more we look, the more we see, leading us to realize: this work is a marvel, full of discovery and surprise.

left: Kate Beck, Wilderness Plan, 2021, oil on linen, 56” x 51”; right: Kate Beck, Wilderness Plan II, 2021, oil on linen, 56” x 51”

“When it really starts to flow, then I feel like I’m there,” she says of her process.

Steeped in painterly concerns and critique, Kate’s practice puts her in the company of such artists as Brice Marden, Helen Frankenthaler, Gerhard Richter, and Jacqueline Humphries; they and others like them form a cosmopolitan art tribe for her.

Hers is an association more obviously with New York than Maine, an observation with which she is quick to concur.

“For years I’ve been seen as a New York artist,” she says.

Though born and living in Maine most of her life, New York is where Kate’s career took off. In 2008, her art work was included in a major painting survey exhibition at O.K.Harris Gallery in SoHo, a famed launching space for emerging artists. From that opportunity she secured gallery representation in the city, had her first solo show, and established a reputation among artists and collectors.

“I became known,” she recalls. “I made close and enduring friends with a great many artists, and became very involved working in this world we shared.”

For years, Kate exhibited in and traveled to New York and Europe, establishing a cultural community far from her home in Maine.

Things started changing for her in 2018. Her longtime New York gallery unexpectedly closed and her marriage of many years ended. Then Covid struck. Homebound in a rental on Maine’s coast, she was unable to travel or exhibit in New York or Europe; feeling cut off and vulnerable, Kate sought healing in her natural surroundings.

“I live at the end of a dirt road, right by the ocean – stone ledge and pine grove and open water. I would sit with my dogs and we’d look out on Will’s Strait, watching the waves and feeling a part of something larger than myself.”

She also took photographs that became the foundation for her Will’s Strait series.

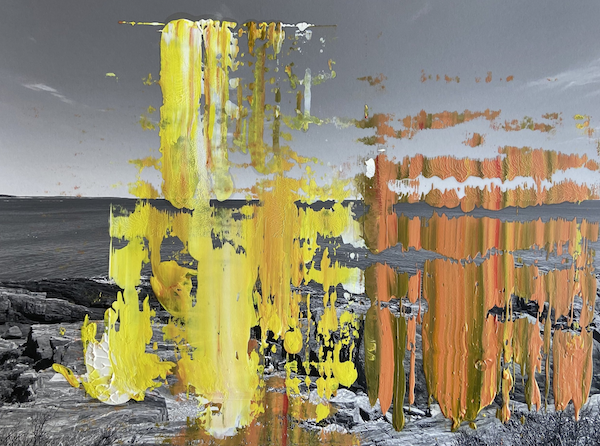

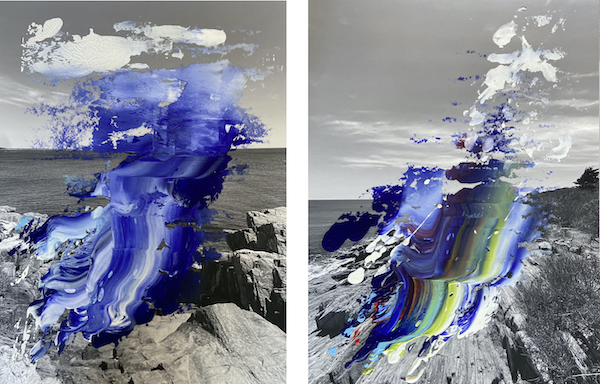

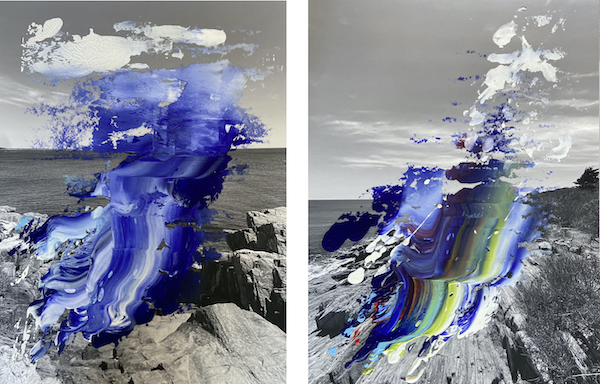

left: Kate Beck, Will’s Strait I, 2022. Digital Archival pigment print, oil paint on Moab paper. 24” x 18”; right: Kate Beck, Will’s Strait III, 2022. Digital Archival pigment print, oil paint on Moab paper. 24” x 18”

With the photographs, it is clear we are in Maine: ocean, sky, and rock. On top of these black and white images, Kate smears and daubs oil paint across the silvery surface in a process similar to monoprinting. The color does not serve the images’ realism, but instead obscures the scenery beneath.

So what is it doing there?

Kate made this series during a hard period in her life, a stretch of time when she drew comfort from the land, specifically from this place in Maine. The photographs are salutes to Will’s Strait, and to them she adds specific colors: blues, greens, and whites; yellows, ochres, and olives. These are the colors of ocean, sky, and rock, intentionally placed by Kate to hover, swerve, and rise. The hues appear to float like pure extraction from within each scene, like the essence of the place.

The paint is literally of Maine, paying tribute to it.

And the same can be said of so much of her work… her dancing ochres and grays, her sweeping blues and greens, all drawn from coastal rock and pine wood – exultations of her native home.

The Will’s Strait series reveals Maine to be the wellspring of so many of her abstractions.

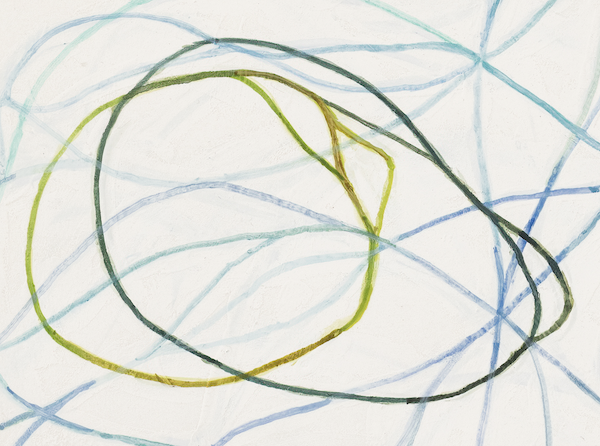

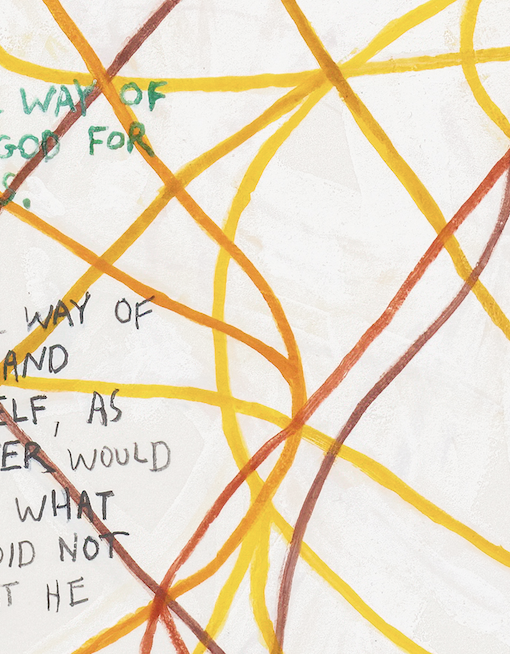

left and right: Kate Beck, Untitled, 2021, oil on linen, 10” x 10”

Kate’s art is complex. By turns conceptual and philosophical, tactile and eloquent, saturated with the artist’s intelligence and emotional life, it defies simplistic interpretation. And yet, on the question of place, Maine is at its core, as it has always been. Kate subtly puts a piece of that in every world-traveling painting she makes.

Kate may be recognized as a New York artist, but in her marrow, she is a Maine painter.

Quintessentially so.