Prologue

So Much Air

“There is a Zen story about a man riding a horse that is galloping very quickly. Another man, standing alongside the road, yells at him, ‘Where are you going?’ and the man on the horse yells back, ‘I don’t know. Ask the horse.’ I think that is our situation. We are riding many horses that we cannot control.”

– Thích Nhất Hạnh, Being Peace

The other day, I sanded down a painting I thought I’d finished a year ago.

It is one of a group of ten I’ve been working on for more than a decade. Every now and then I’ve trotted them out, tried again, made perhaps some small progress. Last year, I was pleased to finally resolve three of them.

Or so I thought.

For months, the three “finished” paintings sat quietly in a corner of my studio. Then, one started nagging at me. (“I am too tight. I am too closed. There is no air.”)

Paintings do not lie. They can show us the way, or reveal when we are lost (or need to be). When they do, we have to pay attention.

So I sanded it down.

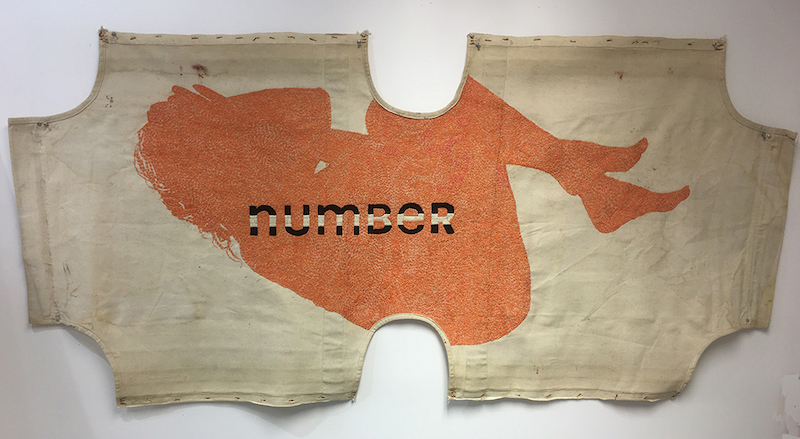

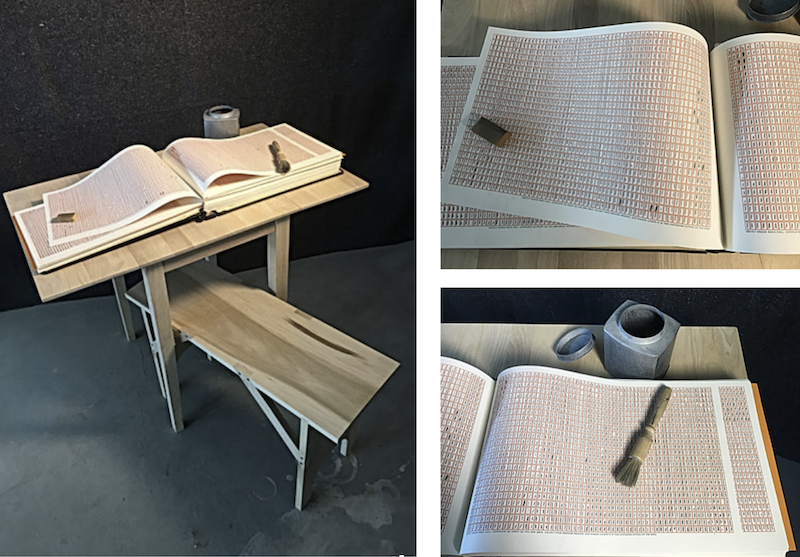

My methodology has always involved erasure: I build a painting up, become lost in its marks, then rub it out, allowing the residue to offer hints on how to proceed. Sanding a painting down is not a rarity.

No, my surprise came in what the backed-down painting said to me: rather than wanting me to meticulously rebuild an image (as has always been the case), the painting was suggesting that the aftereffect of the erasure was the arrival.

It wanted me to mostly leave it be.

The thought went against every fiber of habit.

What – just let it go? Hands off? Surrender to the accidental?

It was clear, and terrifying.

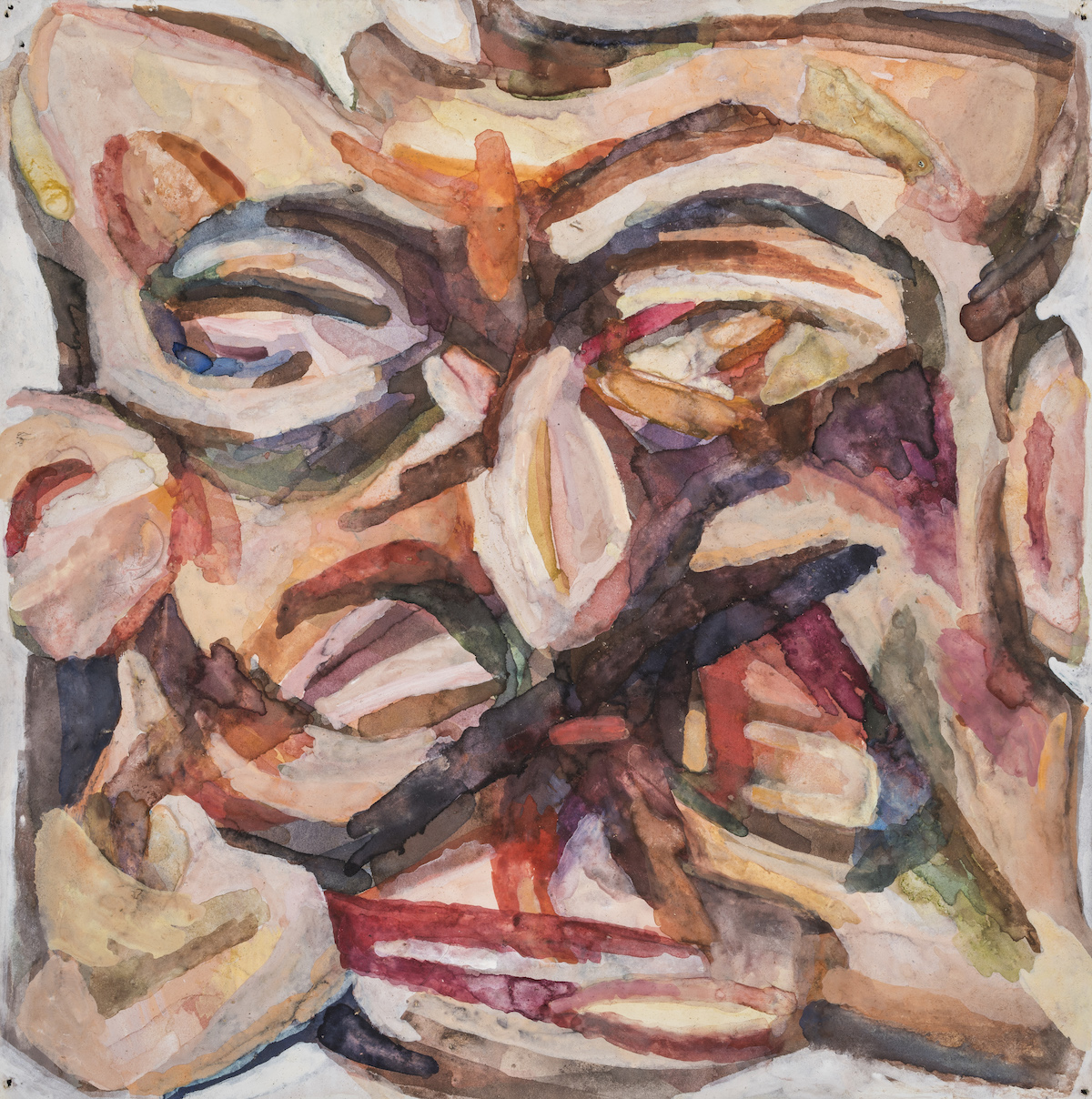

I recalled something I’ve observed in certain painters’ works as they aged: a softening of brushstroke, a relaxation of finish. The phenomenon is not universal, but it’s common: older artists loosen up.

At 80, Alice Neel leaves drips of blue and stains of yellow bleeding across her raw self-portrait’s unfussy surface; just a few years from death, Rembrandt lays down paint seemingly willy-nilly, a flurry of motion magically coalescing as form and light; Palmer Hayden as an old man makes Blue Nile – all pattern and color, line and rhythm, the realism of his prior career a mere footnote of huts and trees in the background.

Tight control gives way to artless touch. Raw passages replace polished outcomes. Technique looks more like surrender than command. The artists are letting go, their work guileless and alive.

We control so little in life, and with age, if we’re lucky, we come to understand this. Our powers wane. The veil thins. As with the Buddhist parable of the man on his runaway horse, release becomes the way.

Reckoning with this truth has been (and is) my task.

I recently wrote about the serenity I now have at home in Maine. The journey here has been dizzying: I had to let go of so much, and all of that frightening release has also brought me so much.

Permitting that release – having enough faith to let go – is hard. Acceptance is hard.

And it is liberating.

Having sanded my painting down, I tremble: there is so much air.

IMAGE CREDITS: Alice Neel, Self‐Portrait, 1980, oil on canvas, 53 1/4 × 39 3/4 inches (Metropolitan Museum of Art; © The Estate of Alice Neel); Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1659, oil on canvas, 84.5 x 66 cm (National Gallery of Art); Palmer Hayden, Blue Nile, 1964, watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper, 54.6 x 70.8 cm (Museum of Modern Art, Committee on Drawings and Prints Fund).