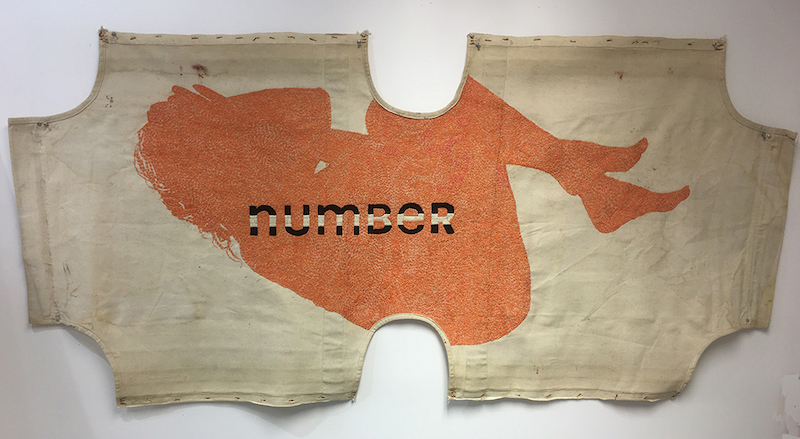

Isolate by Ed Epping, 2018, vintage canvas cot cover, hand-embroidery stitches, 67” x 32” unstretched

It’s a numbing number: 100,000.

That’s the number of people in solitary confinement in US prisons on any given day. It is also the number of hand-sewn stitches artist Ed Epping uses to embroider the solitary figure depicted in his piece, Isolate.

100,000.

*****

How do you translate potent data into something that is also visually interesting?

That was the challenge Ed faced when he began exploring over-criminalization and mass imprisonment in the United States in 2015 with The Corrections Project.

“You have to first catch a viewer’s eye, then—from that—trust that curiosity leads them to want to understand what the art is about.”

He hit the mark with Isolate, which hooks the viewer instantly: The jumpsuit-orange silhouette of a solitary female figure is curled in the fetal position on a vintage canvas cot cover, the word “NUMBER” in prison-stripe black and white branded across the center

The visual alone is compelling.

And then the viewer learns it’s composed of 100,000 stitches sewn in a basic tally-mark pattern suggesting the marking of time.

Then the story behind those stitches: each represents one of the 100,000 people in solitary confinement, living in rooms no bigger than closets 23 hours a day and deprived of all we think of as humane.

And then that word: “NUMBER.”

“There’s this double meaning,” notes Ed. “Depending on how you see the word, it can mean a different thing.” An objective reader may focus on the data and see a numeric reference, but “some who have been in the position the work depicts may read it as about numbness. That’s why I am attracted to heteronyms; they don’t decide how they are to be read.”

*****

Although The Corrections Project addresses a pressing social issue, Ed’s focus on the topic is rooted in personal experience.

“In 1956, when I was 7 years old, my father was sentenced to 5½ years in prison for defrauding funds from the state of Illinois,” he recalls. “He was an accountant, and was clever and manipulative; he knew how to manage numbers.”

Within six months of entering incarceration, Ed’s father became the bookkeeper for the prison warden and within three years he began living in the prison greenhouse, removed from the general prison population in relative comfort.

“It was because he was white,” says Ed, noting that his father’s privilege touched him and his mother, too. “While he was imprisoned we never had to leave our upper-middle class home; we never were hungry. We weren’t wealthy, but we were privileged,” unlike so many families of the incarcerated.

For decades, Ed’s formative childhood experience percolated. As he approached retirement from years of teaching art, he looked beyond his father’s comparatively easy imprisonment, focusing instead on the huge toll of mass incarceration on those most commonly victimized by it.

“Though The Corrections Project is prompted by my relationship to my father’s prison experience, that’s not what it’s explicitly about. I wanted to explore incarceration and over-criminalization more broadly, and look at the populations most impacted by criminal justice abuse: Black and Brown people” (who are five times more likely than whites to be incarcerated).

“Understanding the complexities of scale is a challenge for most individuals. We hear large numbers and find it difficult to imagine how that quantity appears.”

*****

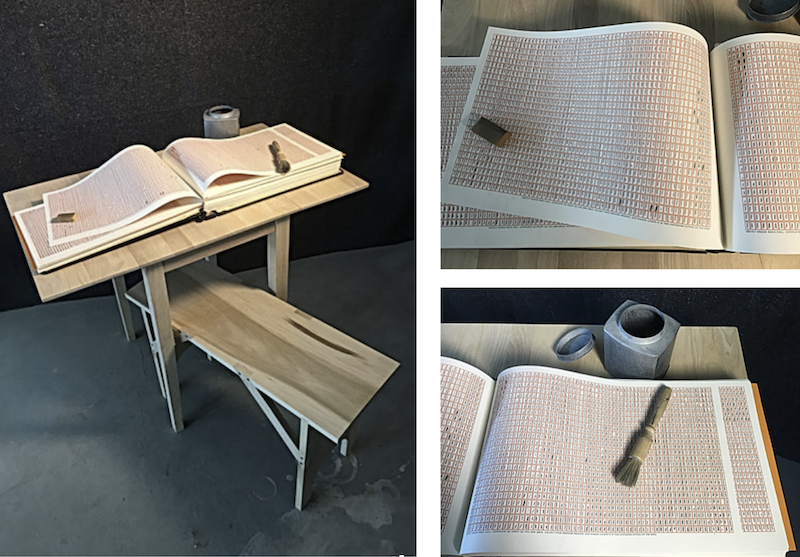

The Abolitionist’s Ledger is another example of a piece animating grim numbers.

The work is primarily composed of an enormous (1500-page) ledger, each page containing 1500 orange-outlined cells. Ed has made a pencil mark to occupy each, a total of 2,300,000 individual marks (one for each prisoner in the United States). The ledger sits on a table along with an eraser, brush, and container. An accompanying bench invites viewers to sit, and at the bottom of each page is a written instruction: “Gently erase each cell. Complete as many as you are able. Collect your erasure residue and please locate in the container sitting on the desk.”

In robotic administrative language, the directive asks the viewer to complete a simple task. But when we recall each pencil mark stands for a life – so easily erased, swept away, and replaced – we are called up short by the horror of our complicity (as citizens) in a coldly bureaucratic system yielding such immense human cost.

The Corrections Project is a tool for advocacy as much as an art project. In his solitary vigil in the studio, with each stitch and every pencil mark, Ed offers an appeal, counting the countless.

Ed Epping is an imagist and activist living in New Mexico who taught art at Williams College for 40 years, retiring as the A.D. Falk Professor of Studio Art in 2017. More of his work including The Corrections Project can be seen at his website.This story is an updated version of an article that first appeared in Bruun Studios’ Yarrow & Cleat in September 2020.