Prologue

Spindrift

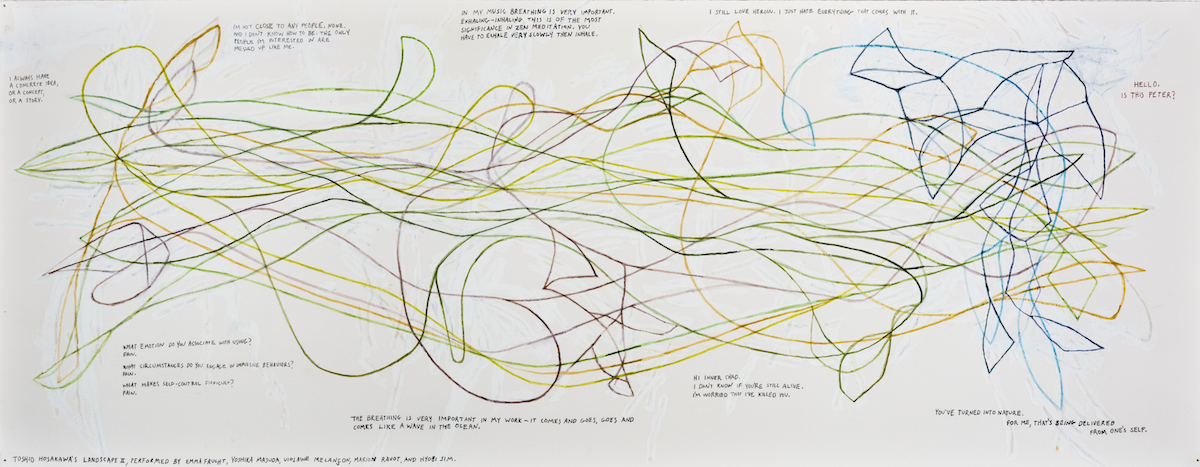

“His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

― James Joyce, The Dead

That’s my great-great-grandfather on the right, Eleazer Hart; one hand in his pocket, the other holding spectacles. He’s standing in front of Hart’s Jewelry Company in Kansas City, Missouri.

The year is 1892.

This past Thanksgiving, we had a reunion on my mother’s side of the family. With a few absent, there were 36 of us: my mother, her brother and sister, their children and grandchildren, some married into the family. A high point was my uncle sharing the genealogy work he’s been doing, including uncovering this photo.

The year is now 2021.

Children of children, parents of parents, together looking backward and forward, finding pattern and rhyme, dream to dream, longing to longing, rise and wane and rise again.

1847: Philip Hart emigrates from England to America. A milliner by trade, he marries Julia Speyer shortly after arriving. Their son Eleazer, born ten years later, gives them 13 grandchildren including my great-grandmother, Hazel Hart, who (according to family lore) was a “singer on the stage” (a bohemian for sure).

Hazel died in 1953 (I never knew her).

I was born in 1963.

In 2024, it will be ten years since Elisif died.

Ten years.

Hand in pocket, does Eleazer wonder at generations to come – at me – as I wonder at him, his wants and dreams? Who does he grieve, as I grieve my daughter?

From here to there, ancestors parade, in grief and grace, in love and loss. Blood and breath and bone – ethereal weight and ineffable light. The me in you, you in me – our sorrows, hopes, beauty and pain in gossamer thread – us as one in velvet whisper, like a thousand white and speckled feathers suspended by air: sunlit.

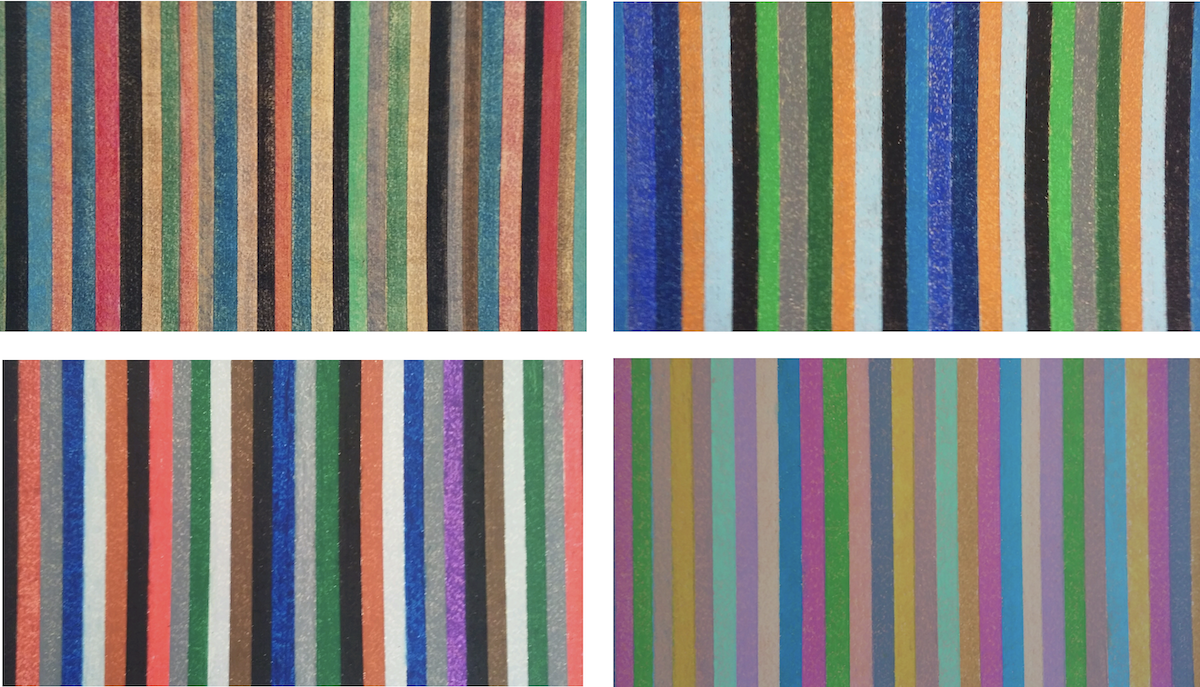

I moved from Baltimore to Maine two years ago needing quiet and solitude, a place to heal, to feel safe opening myself to myself – a space to make art. I came to Maine for sanctuary, and found it. Paradoxically, it has been in the solitude of my studio – physically away from my community and people – that (through my art) connection has taken the place of apartness.

Spirits in attendance – every day.

This has become the stuff of my art: our vivid and linked humanity through birth and death – in stumble and stand – in walk and tears.

I find my way – we find our way – ancestors in pocket.

—Peter