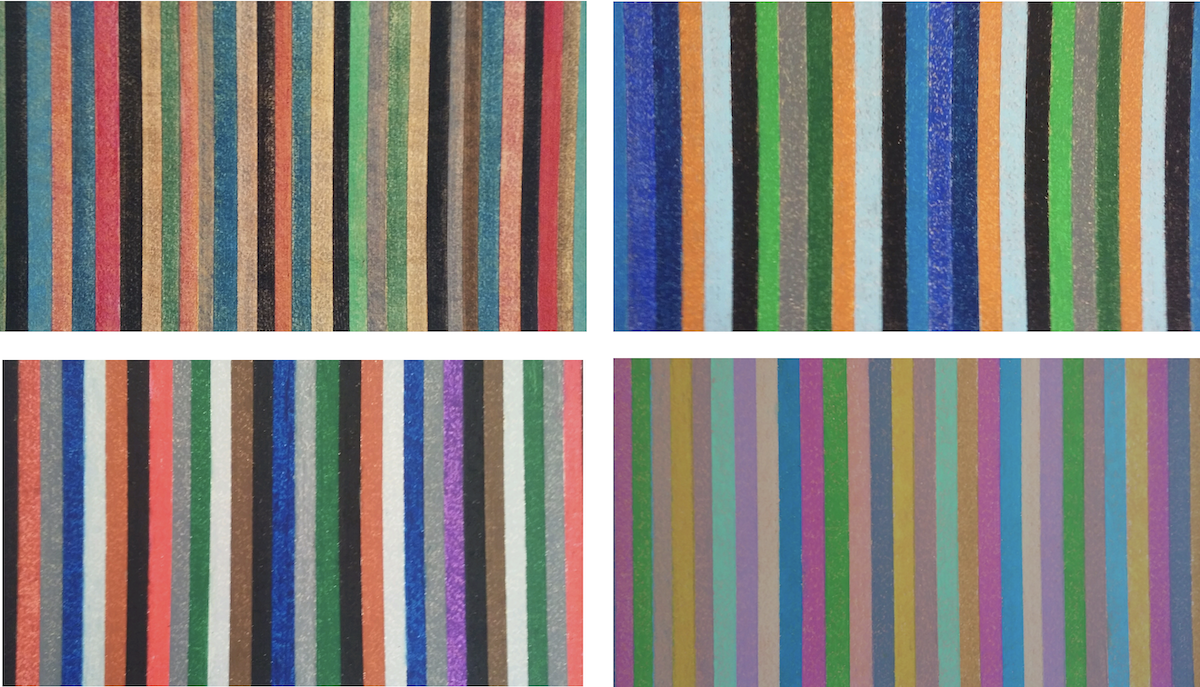

Notes and Chords by John Viles, each 11″x15″, oil pastel on paper, 2021. Clockwise from upper left: Page 5, Page 6, Page 10, Page 7

Notes and Chords began simply enough: John Viles missed using color.

“I had completed 24 drawings in black and white and was just itching for color. I got out a bunch of oil pastel, sat down, and started drawing,” he says.

So John drew – one light-filled stripe after another.

He had no grand plan beyond the act of creating. It was familiar, making art just for the sake of making it. The new drawings brought him back to early childhood at his grandmother’s house, where she would settle him down with art supplies before going about her housework. While she did her chores, Chopin played on the stereo and John drew just to draw – like play.

Color has spoken to him ever since.

“I love to work in color – it’s something I am most drawn to – its optical qualities, its presence in the world or lack thereof,” he says.

But when John put his first few new striped drawings up on the wall, something unexpected happened.

“I started to see melody – as if the colors were piano keys speaking back to me. They seemed to be harmonizing, and that gave me the notion of working with a musician.”

John began looking for a collaborator and found one in composer Woody Lissauer, whose work he admired and who he tapped to compose 3-minute pieces to accompany each painting. The idea of having music composed to go with his own art was new for John, but the interconnectedness of art and music was not. His time at his grandmother’s house was foundational, of course, but he also had a striking moment of synesthesia at a Mark Rothko retrospective in 1998.

“In the final gallery, I started to hear Mozart’s Requiem Mass in D minor in my head when I looked at the work, and it started to play louder. It struck me: these were Rothko’s last paintings before he died of suicide, and Mozart’s unfinished requiem mass was his last piece. It all connected for me.”

But the concept of using music with his own work did not arise then, despite the powerful experience. For years the idea lay dormant while his art took all sorts of other directions. From the conventional figurative work of his student days at Kansas City Art Institute in the late ’70s to elaborate installations addressing issues such as the Chernobyl nuclear accident in the ’90s, his work ranged widely. Much of it was non-objective art rich in color and personal significance, but none had included the element of music – until now.

So why the shift with Notes and Chords? The answer may lie in newly awakened memories of his grandmother.

“She wanted to be a violinist, but she was from a tiny town and her parents didn’t want her to go away to the big city to study music so she put her violin away for good,” he says.

She put her violin away for good.

The woman responsible for introducing John to art making and the joy of color, the one in whom a connection between art and music is forever linked for John: she put her music away, seeing her own musical dreams dry up even as she watered artistic seeds for John.

Having started modestly enough, Notes and Chords has grown into something more than an antidote to color missed, for it not only recalls John’s earliest memories of art and music, it also – in a magically realistic way – brings his grandmother’s spirit and the spirit of her music to life.

And there is no better reason to make art than that.

—Peter