Prologue

Out of Place

“He ceased to be lost not by returning but by turning into something else.”

― Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

This monthly email now has a name: Out of Place.

Let me explain.

It starts with my day.

I wake early, it still dark outside, my bedroom cold (I like it that way). After showering, I fire up the wood burning stove, then an hour of stretching, followed by exercise (this morning I shovel the drive; it snowed yesterday). Workout complete, I make my breakfast: fresh coffee with plenty of cream alongside berries, banana, and yogurt, all garnished with freshly-shaved cacao – the block of it a gift from my youngest daughter. I eat to music on Spotify (Gordon Lightfoot just now), sit at my computer, settle into my day, here at this place.

The same each morning.

My rhythm.

My home is surrounded by trees, the only visible house diagonally across from me on the other side of a shared private road, four other homes further along before the road ends at the lake. I rarely see my neighbors; it’s quiet here. Inside, I have made things as I like them: art on the walls, much of it by my eldest daughter and uncle; framed photos of family and friends everywhere; antique toy soldiers from my father and Oaxacan figurines (a gift from my mother) scattered here and there. In winter, I like to light candles, letting them burn through the day.

All this makes my home – my sanctuary, everything in its place.

I have not always lived this way.

My solitary move to Maine has taken place in slow motion over the past several years, its stuttering pace mirroring so much other drawn out and excruciating change in my life – what I do, who I am with, how I see myself – all like molting: a bit sloughed off here, another bit there.

Metamorphosis at a glacial rate, though instigated by a lightning strike: “Hello, is this Peter?”

My eldest daughter died eight years ago next month, and the world never seemed more wrong than it did that day – suddenly and completely out of place. It took me time to recognize just how fully so… to allow it… to admit it to myself. To release in totality what had been and could no longer be: my notion of family (a place at the table removed); my closely held values (wrong becomes right as wrongness becomes real); my faith in another chance (no bargaining back listening together to If You Could Read My Mind).

Out of place all at once, everything torn, reckoning with it in fits and starts, from trauma to here – to this new place, like a fresh dawn: that’s my story of transformation.

I name this monthly missive Out of Place because I have emerged from out of place, whole and healed, and now – out of this place – I write, from me to you, with love.

—Peter

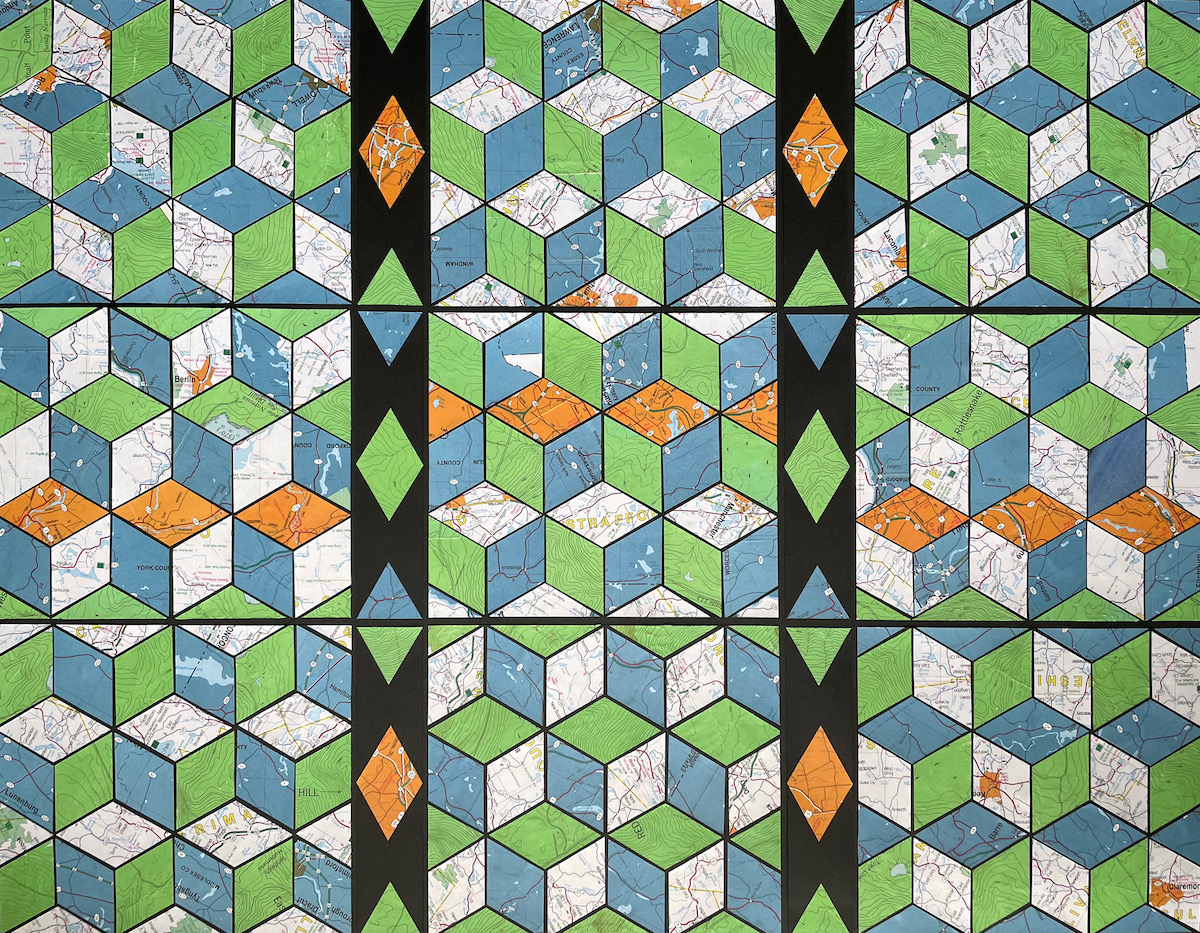

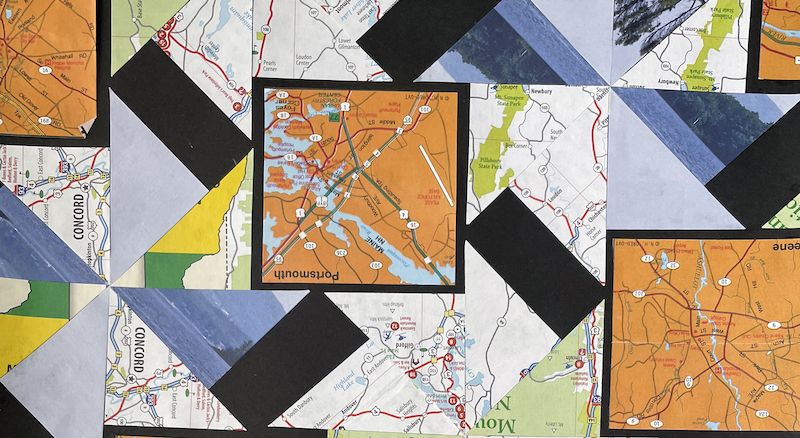

Detail from the first piece circe made cutting up an actual map

Detail from the first piece circe made cutting up an actual map