Prologue

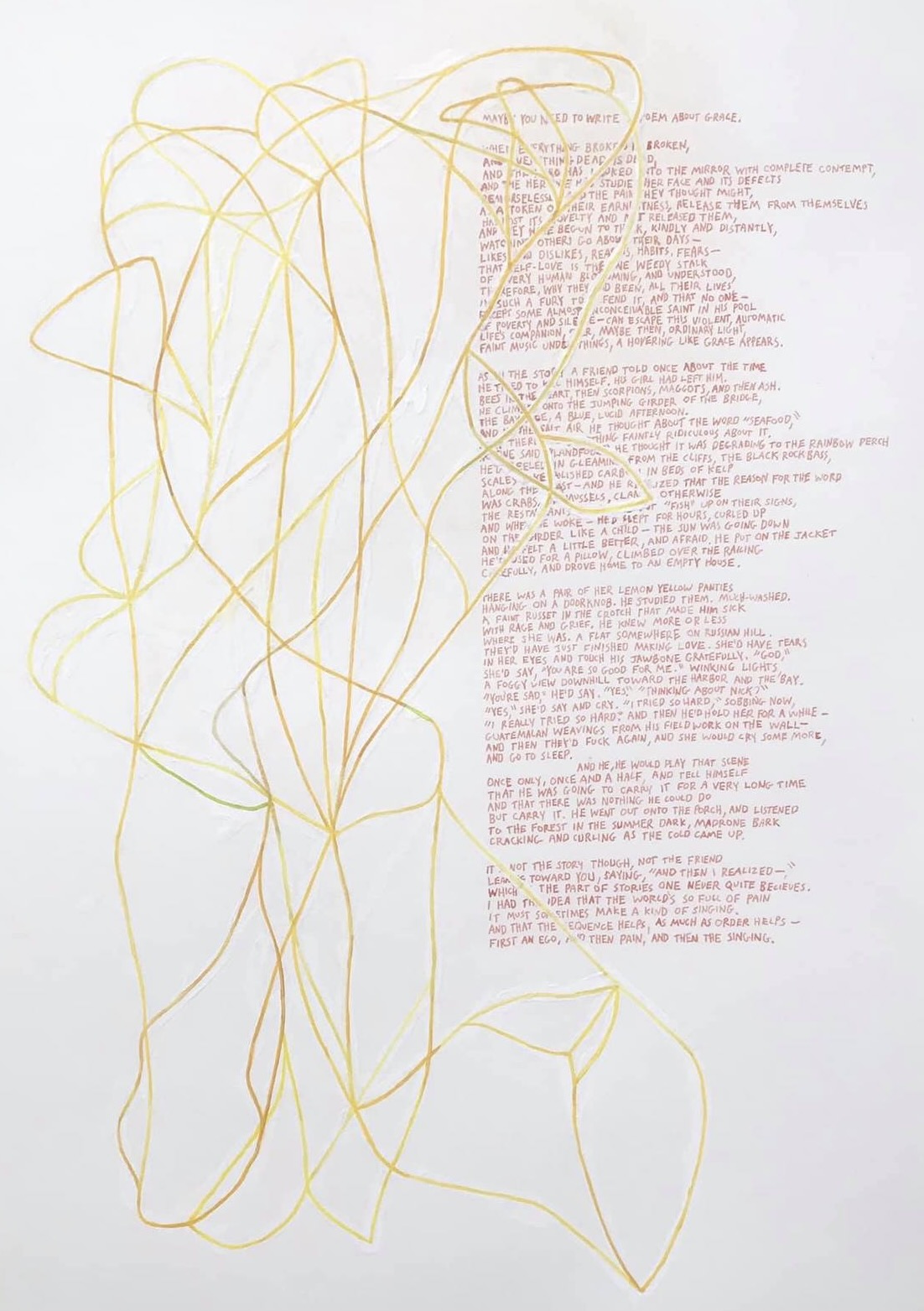

Faint Music

‘Faint Music’ by Robert Hass by Peter Bruun

“And in the salt air he thought about the word ‘seafood,’

that there was something faintly ridiculous about it.

No one said “landfood.” He thought it was degrading to the rainbow perch

he’d reeled in gleaming from the cliffs, the black rockbass,

scales like polished carbon, in beds of kelp

along the coast.”

—Robert Hass, from Faint Music

I first read Faint Music by Robert Hass well over a decade ago. It struck me then, and sticks with me now. It’s meant different things to me over time: as with all good art, as I change it changes with me.

For a long time, it was the final line:

“First an ego, then pain, and then the singing.”

Then, my eldest was struggling with substance use disorder, along with all the attendant behavioral issues that come with it. I thought (and still think) that sequence of three—first an ego, then pain, and then the singing—spoke directly to the arc from use to dependence to recovery. I prayed for my daughter to reach the singing (she never did).

Then, for a long time, this:

“I had the idea that the world’s so full of pain

it must sometimes make a kind of singing.”

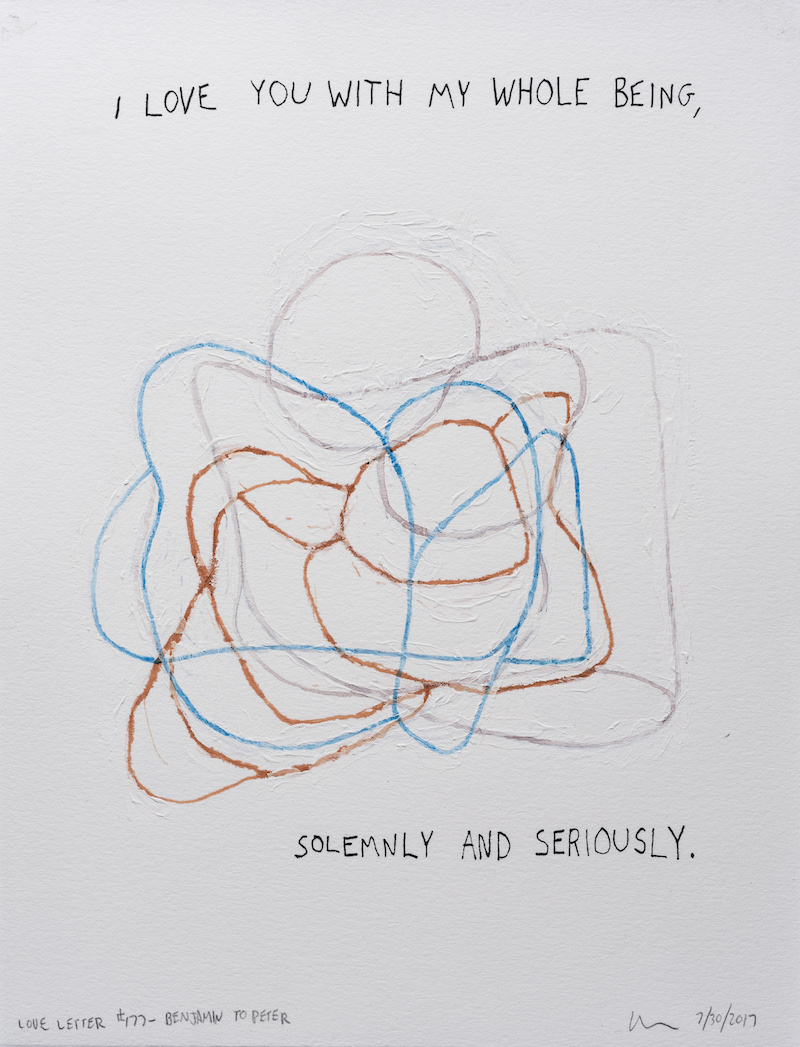

My story, since my daughter’s death. (My fractured family; so much art.)

There’s a lot I don’t understand in the poem, but that’s okay; its emotional energy feels so right, its aura of pathos. Its details.

“There was a pair of her lemon yellow panties

hanging on a doorknob. He studied them. Much-washed.

A faint russet in the crotch…”

There are things we see, hear, or learn in this world that turn our lives inside out, perspectives a-kilter as we’ve not known before. Art does that, and so do life experiences: discovering Faint Music; coming across Cezanne’s Vase of Flowers; the phone call I got nearly 8 years ago; seeing those photos yesterday.

The hum of it all makes us who we are. Lands us where we are, with what we have.

“Faint music under things, a hovering like grace appears.”

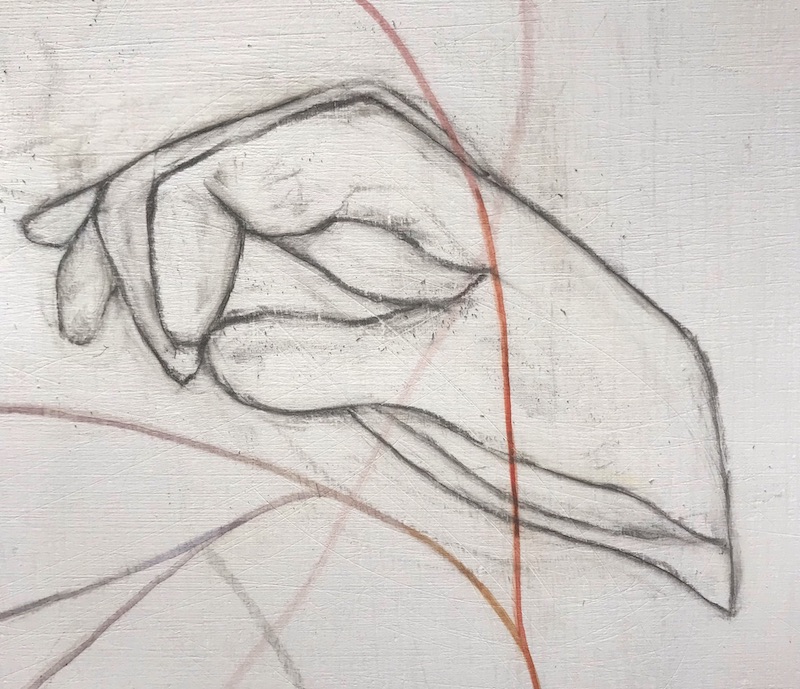

What I love about poetry—what I love about Hass’ poem—is its sensory detail. Not just any word will do, for each is asked to carry weight. We, in turn, are asked to notice; not gloss over.

When I stumbled upon photos of my daughter yesterday I had not seen before, they were upsetting at first: raw, a view of her I’d rather expunge (sunshine of the spotless mind).

Too much information.

And yet.

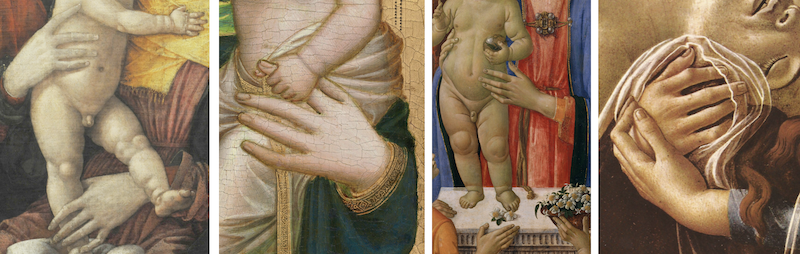

With nothing to challenge how I remember her, recollection sets like cement, ossifying into a kind of hagiography. With time and gloss, details give way to general abstraction. She becomes as two-dimensional as a textureless frieze; as general a notion as “seafood.”

And that’s not how I want to remember Elisif: I want to be faithful to recalling who she is in meticulous detail. In granular truth, those photos and all.

What I cherish in the excerpt I chose for the epigraph above is that it takes on the diluting impact of a word like “seafood,” and instead thrills in precision: the rainbow perch “gleaming from the cliffs”; the black rockbass with “scales like polished carbon.” The passage sings of singularity, of paying attention to all the particulars, implicitly imploring us to do the same.

For in paying attention where color and nuance abide, in holding close the coarse with the couth (twinned as night and day), we touch the stuff of life.

In all its melancholic hum, its majestic beauty, we hear faint music.

—Peter