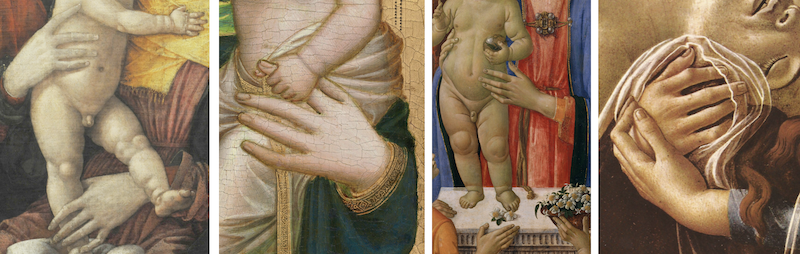

In recent months, I’ve been enamored of European Renaissance paintings, particularly (though not exclusively) those with Mary and Jesus as subject, for what the hands in them are doing is extraordinary.

Reaching. Twitching. Intertwining. Floating. Flirting. Grasping. Dancing. Playing. Delighting. Grieving. Touching.

The hands do all the emotive work, and they are beautiful.

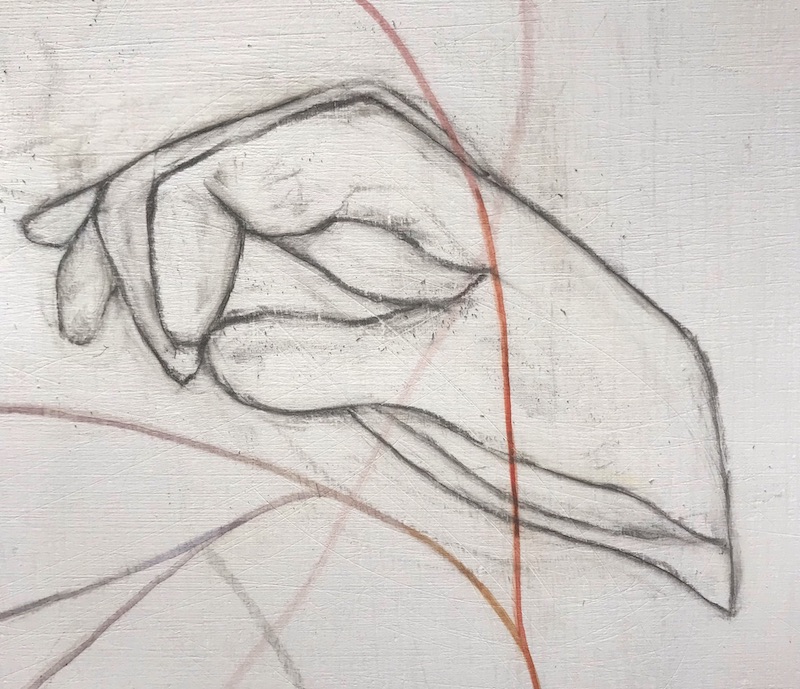

In what I am working on now, I draw inspiration from such works, appropriating passages as I go (the image atop this article is an example, a detail from a recent work-in-progress). I am not sure if I ought to think of these works as homages, or visual conversations with past works, or fresh takes on old truths. I don’t think I’m merely copying, or leaning overly heavily on the crutch of association with such spectacular works (reflected shine from celebrity friends)—at least I hope that’s not what I’m doing, though I cannot be certain.

No, the only place certainty lies here is with what I’m most drawn to.

The touch of finger on finger, hand on hand, body to body. The touch of my mark, be that a fluid line in oil or a vine charcoal tremble. The touch of paint and charcoal on gesso ground—sanded, ribbed, and rubbed. Delicacy; intimacy.

The meaning of touch. The power of touch.

I remember the violinist Isaac Stern in an interview explaining the job of the musician in relationship to the score. He shared as an analogy saying the words “I love you”: you can say it in a dead-pan voice (which he demonstrated robotically: “I-love-you”), or you can say it with feeling (“I LOVE you!”). It’s all in how you say it; it’s all in how you play the music.

It’s all in the touch.

—Peter