Prologue

Summer Weather

“I am the Poem of Earth, said the voice of the rain”

— Walt Whitman

It was a wet July—record rain in many parts of Maine.

Today, the sun is out.

Other than my daughter Elisif, I rarely speak publicly about my family. This past week, celebrating another daughter’s return to the U.S. from India, I made an exception, writing about her arrival on Facebook. Nearly 400 people “liked” the post and over 100 commented—more responses than I’ve ever had before.

What is that about?

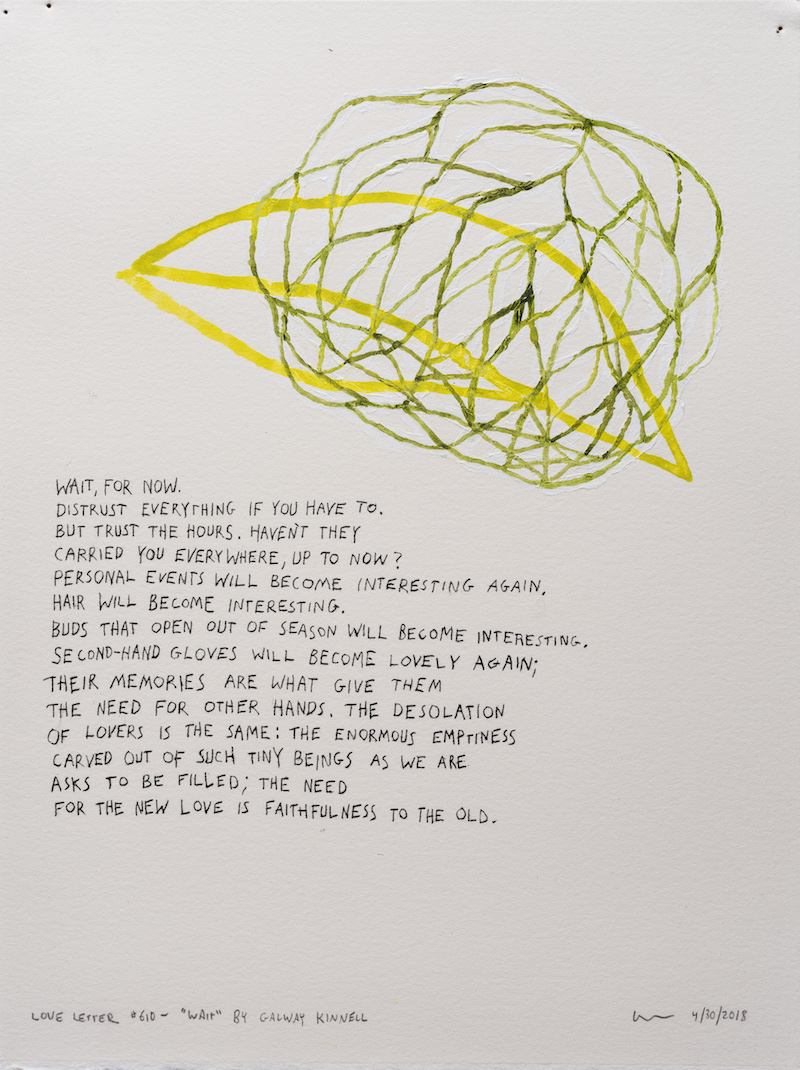

I know weather changes (you know weather changes). Fast and sudden, thunderclaps emerge; skies draped in grey, at times seemingly without end.

That’s why beams of sunlight are so universally welcome, their transience the very reason for celebration. So the wandering child returns, and 400 voices join in “hallelujah!”

As always, weather changes: now, just as COVID seemed to be waning, the delta variant rises.

New weather—a foreboding wind bringing with it fretful cries of “here we go again!” For some, the “again” is a reactivated fear of the virus, at times marked by a judgmental outlook verging on the hostile toward those resistant to masks or vaccines. And for that group, the “again” may be fear of being forced to cede personal beliefs for a purpose they have trouble rallying around.

Like shearing wind, values collide. (Planes can crash in wind shear.)

Weather comes.

When it shines, it brings us together in celebration (my wandering daughter returned). When it storms, our safety seems threatened.

But it’s not the weather we ought to concern ourselves with; that is outside our control. Rather, our challenge lies in how we manage ourselves in the elements, for preserving our humanity and compassion toward one another in battering rain or sweeping wind serves us all.

Weather is life, and it can test us. Let’s work on thriving in it together.

—Peter