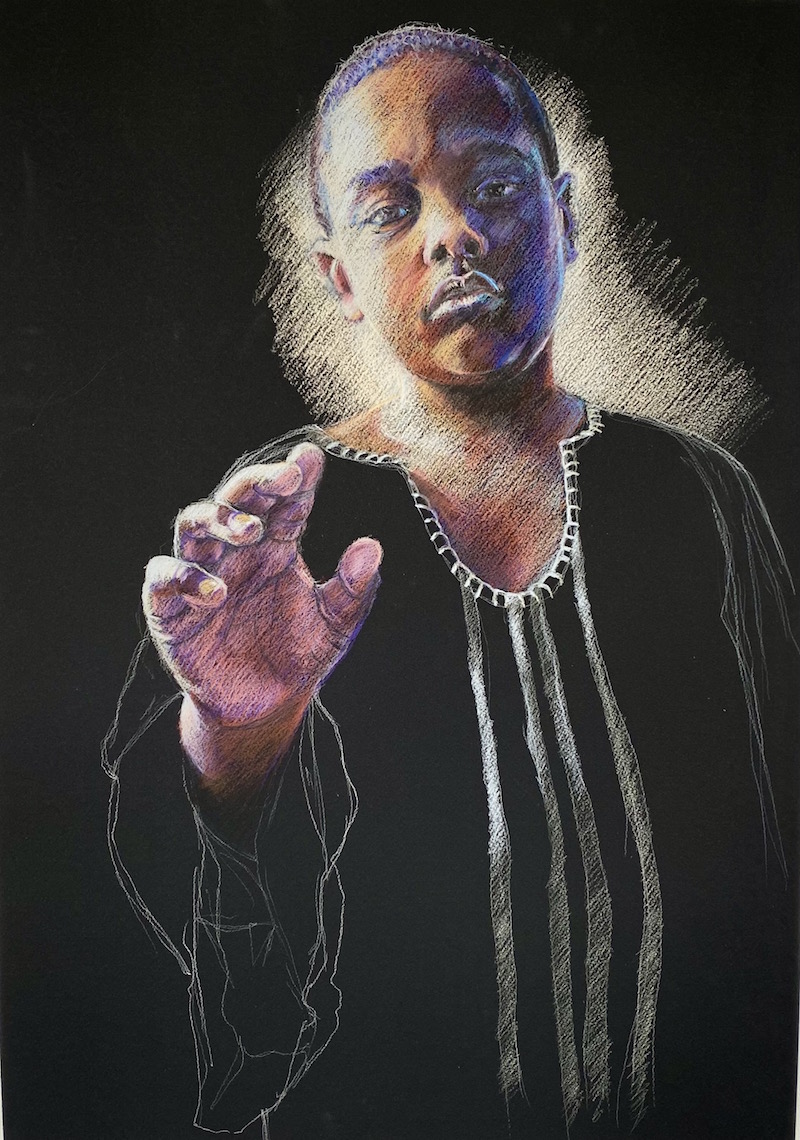

This month’s Cameo features The Light, a drawing recently completed by Ernest Shaw during a residency at Mass MOCA.

On July 18, Ernest Shaw began a drawing of his son, Taj Amir Shaw.

“It’s been almost 16 years since he transitioned,” says Ernest. “I’d been carrying this image a long time. It was his birthday. I just went for it.”

And so came The Light.

The image is striking: a boy wearing a dashiki, hand outstretched toward the viewer in a gesture akin to benediction, a glow around his head. Simple, yet powerful in presence.

Ernest saw his residency at Mass MOCA as an opportunity to try new things, so in making the piece he worked with Caran d’Ache Luminance pencils, a new brand to him. He was also experimenting with black paper.

“The drawing was an exercise in light,” he says. “The physical process I used with the materials is a reversal from the usual way for me: I am building the light from darkness rather than what you do with a white piece of paper.”

An exercise in light, and more than that too.

Over the years, Ernest has made only a few works depicting his son. He has portrayed his daughter many times, and has made a vast array of figurative art replete with references to cultural identity and African-American ancestry: James Baldwin; Baltimore’s “squeegee kids”; overlays of African masks; overt symbolic clothing or poses. An accomplished muralist, Ernest has adorned neighborhoods in Baltimore and beyond with imagery of African-American people and history.

And through all of this work, only rarely has he portrayed his son.

“I’ve made less than five drawings of him, and those have been so personal I keep them close to the vest. I’ve wanted to do this one for a long time, and I’m in a place now where I can do it. It served as therapy for me to create that piece. Building from dark to light is an emotional journey, and it’s been my personal journey since my son transitioned.”

Since his son’s transition, Ernest’s attitude has shifted from believing to knowing “there’s no death in dying. I no longer allow my mind to shut down in ways I used to allow.”

The Light, he says, is his “love language”—his way of declaring eternal and living love.

“That’s my evidence—it’s the piece. Not anything I can express verbally.”

And the piece is unequivocally about presence.

While African-American heritage and pride remain core themes to his work, Ernest embraces a mission that goes beyond racial or ethnic identity.

“My most recent artist statement focuses on how I am attempting to tap into the humanity of the viewer by exhibiting the humanity of the subject. What resonates is the human element no matter the race or place in the world. It’s about one humanity.”

With The Light, we all stand in Taj’s presence and receive his blessing. We are all part of his human family. And we are reminded, perhaps, of those we love who are departed, and still with us.