Prologue

Persistence

“Perhaps it is not odd, at the end of this tragedy, where nothing much was left of the elite who came from the sky, but courage struggling for oxygen, that I have often found myself thinking of my wife on her brave and lonely way to death.”

— Norman Maclean, Young Men and Fire

I’m having work done on my house, and a patina of drywall dust coats everything. There are holes in my ceiling where overhead fans once were. After a run of hot, humid days, mold has appeared on my carpet. The lawn needs mowing again.

I tip my head back and squint at the screen as I write, trying to bring words into focus (I’m waiting for new glasses; I hope they help). I use only the two middle fingers of my right hand to type, saving my arthritic pinkie and index finger from the pain. As I sit, I notice numbness lingering in my upper left thigh from an injury.

As challenges, I know my aging body and work-in-progress home are small—I see that when I lift my head and look around.

A friend texted me last night. “Peter I’m settled in. I’m so exhausted.” Tossed out of another apartment with all she owns in two duffle bags, she’d made it to a Motel 6. On Monday, she’s due to check-in to rehab—again.

The biopsy came back positive and now someone I love has a follow-up appointment in two weeks. It’s too soon to know what comes next.

Another person I care about, Shabana Basij-Rasikh, founder of the first and only all-girls boarding school in Afghanistan, was trapped with her students in Kabul as the Taliban took over. Though they made it safely out of the country, their future is uncertain.

Today is September 11. I don’t personally know anyone who perished twenty years ago, but I am close to people who do. For them, this day is heavy—it always is.

The world is full of setbacks and decline, waste and loss.

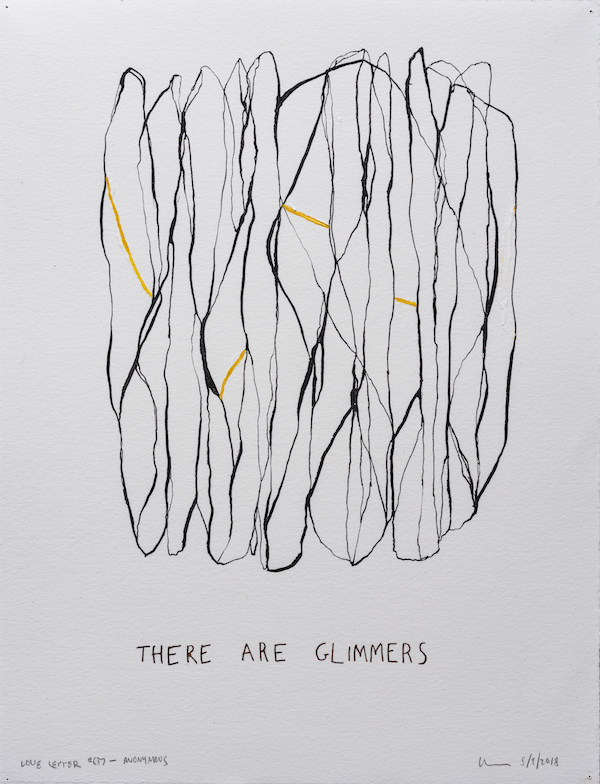

And yet we persist.

At the end of Young Men and Fire, Maclean writes of his wife’s “brave and lonely way to death.” Unbeknownst to the reader, it’s the death haunting the entire book, a death he needs to make sense of.

In the book, Maclean imagines the last living moments of the young men of the title—firejumpers facing the deadly Mann Gulch fire in Montana. Like a forensic investigator, he considers how their bodies fell, where they were on the mountainside, their distance from the crest as they vainly ran from advancing flames.

He marvels: they never had a chance, and they never gave up. To their very last breath, they never gave up.

Like his wife. Like my friends above. Like me. Like all of us.

We never give up, because that is what life requires of us. We persist to live—persistence is living.

And that makes it beautiful.

—Peter