Prologue

Nights and Dreams

For a while it was forever, and then things started to fall apart.

– Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

I wake from another night of dreams.

Windows up, my room is cool, the air damp. I roll to my side, fluff a pillow, lay my head down, close my eyes, only to open them a moment later: the gray light of an early overcast morning is everywhere.

I wonder at my life: Here. Now. This.

On the chest of drawers in my room is a photo of my mother from perhaps 50 years ago. I’m struck by just how much she looks like my sister, Kit. At the time the photo was taken (so long ago), Kit had not been born yet (she has daughters of her own now).

I think about all the change my mother has been through in her nearly 85 years.

She: the eldest daughter in a family of five, dad off to work in the city, mom at home, more pet dogs than siblings running about.

She: a newlywed and living in Denmark, tending to her first husband’s doddering dad; one child, and then two.

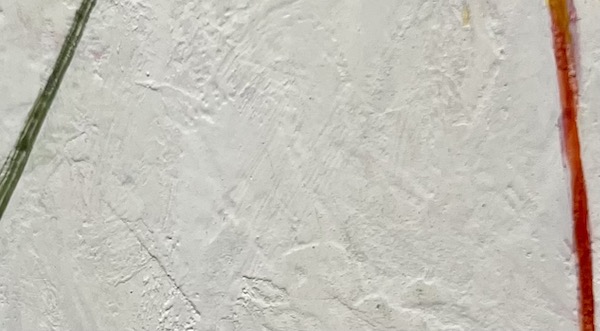

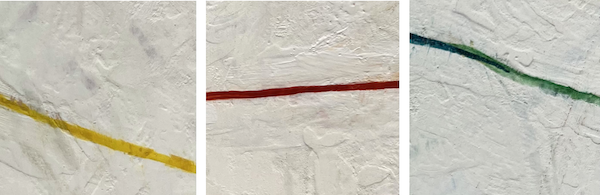

She: back in New York, second husband (him with a new pair of stepsons), chipping plaster in their new Chelsea home, revealing the old brick beneath.

She: managing teens and toddlers, nannies come and go, friends in and out, business dinners hosted for her husband’s clients (they are a team).

She: widowed yet peripatetic, photography and trips around the world, holidays overflowing with children and grandchildren, presents piled under Christmas trees.

Her life is quieter now.

In my own gray-lit room, my bed cozy and warm, I want to stay here. I want it to be like it was, or stay as it is. Anything but change.

(“For a while it was forever, and then things started to fall apart.”)

When I was a small child, my parents divorced. I have no real memory of it – just a vague notion of once asking when daddy was coming home. I don’t recall how mom answered, just that seeing daddy meant going to his home now. I think about that small child, how harrowing change – any kind of change – became for him.

I am still that small child, dreading change.

But then I think of James Baldwin’s words:

“For the truth, in spite of appearances and all our hopes, is that everything is always changing and the measure of our maturity as nations and as men is how well prepared we are to meet these changes, and further, to use them for our health.”

In recent days, I have become aware of a knot inside – a sticking place where something unresolved from my past is tangling my present. I feel frozen in sadness, stuck in my eddy, unable to move on. I am clinging to something – a change I’ve resisted naming or acknowledging – and it has been haunting my nights and dreams.

Clouds now cleared, out of bed and fully awake in the summer sun among singing birds, listening to Schubert’s Nacht und Träume, I write to name the knot, to release what haunts me:

Me: young and in love, silently eavesdropping from the other room, her liquid voice a whisper, guitar chords soft; I melt.

Me: older now, listening to a friend on guitar, my new love joining in song (an echo from a life ago).

I am overswept by jarring sadness, by the memory of all I have lost, all that changes.

With tear after cleansing tear, the knot loosens.

It’s a new day, and I am okay.