“Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak knits up the o’er-wrought heart and bids it break.”

– Macbeth, 4.3.245-246 (William Shakespeare)

The other day I recalled a dream I had shortly after Elisif died.

I was back at college, walking across campus, headed toward my dorm room. The campus was large enough that traversing it meant passing a number of buildings, and rather than walk around them I decided to shortcut by entering each from one side and coming out the other: in through a door, around a set of steps, down a hall, and out the other side. Each time I exited, there’d be another building in front of me, so I’d repeat: in, around, down and out; in, around, down and out; in, around, down and out.

There was no end to this.

I woke up, terrified. My daughter was still dead, and I felt so terribly lost.

I do not know how I would have survived those days had it not been for the art I made.

*****

I recently read Rebecca Solnit’s new book, Orwell’s Roses. In it, she shares an anecdote from a judge at the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague presiding over testimonials from victims of war atrocities. When asked how he could stand listening to such heart-rending stories, he replied: “As often as possible I make my way over to the Mauritshuis museum, in the center of town, so as to spend a little time with the Vermeers.”

Solnit notes of this anecdote “that human beings need reinforcement and refuge, that pleasure does not necessarily seduce us from the tasks at hand but can fortify us.”

The judge found restoration by turning toward art.

*****

As I write, my partner (Leigh) is doing some volunteer work in Rwanda for a school she’s been involved with since its inception, School of Leadership, Afghanistan (SOLA). When the Taliban overtook Kabul this past summer, the entire school community managed to flee Afghanistan, each person bringing with them a story of escape. Their host country – Rwanda – is of course no stranger to trauma: in 1994, one million people were brutally murdered in the Rwandan genocide.

Leigh cannot turn left or right without hearing another harrowing tale: one new Rwandan friend attacked with a machete and left for dead in a mass grave at age 12; another who lost 7 siblings and both parents and later fought to bring their killers to justice; the school’s entire student body – dozens of girls – with their families back in Afghanistan, knowing the impossible choice to leave was the only way to stay safe.

At the school, the students have told Leigh their favorite subject is art.

*****

I recently watched Summer of Soul, the critically acclaimed documentary directed by Questlove about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. The festival took place in a particularly fraught time – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assissination from the year before still felt raw, and social unrest was on the rise nationally. Event organizers had gathered support for the festival in part by selling the idea that such a thing could help avert summer violence – that music could offer hope, love and community in place of cynicism, alienation and riot.

It worked.

Nothing brings that truth home so clearly as the moment Mavis Staples and Mahalia Jackson sing Precious Lord, Dr. King’s favorite hymn, to commemorate the first anniversary of his death. An audience member later described the moment as “an eruption of spirit,” transforming a summer of disquiet into the Summer of Soul.

That’s art.

Before grief and atrocity, barbarity and dislocation, soul’s famishment and pain, we need balm and succor – words for our sorrow, attendance to our “o’er-wrought” hearts.

So we turn to art, always there for us, and saving me every time.

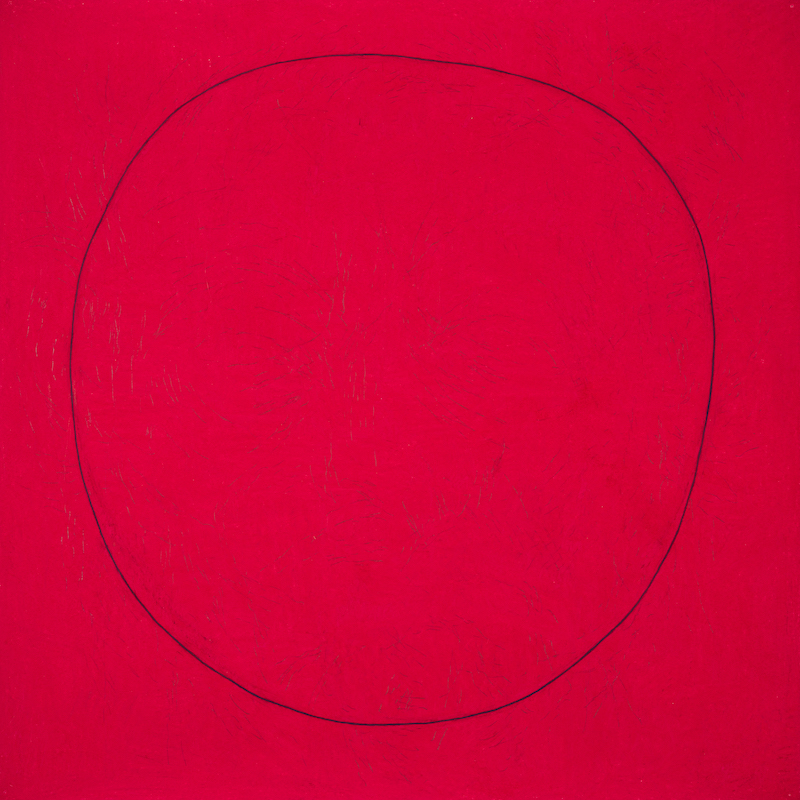

(I made the drawing above not long after Elisif died: a black, static circle on red ground – Elisif passed. It became part of the intermedia art installation, Elisif’s Story, the audio track of which you can hear here.)