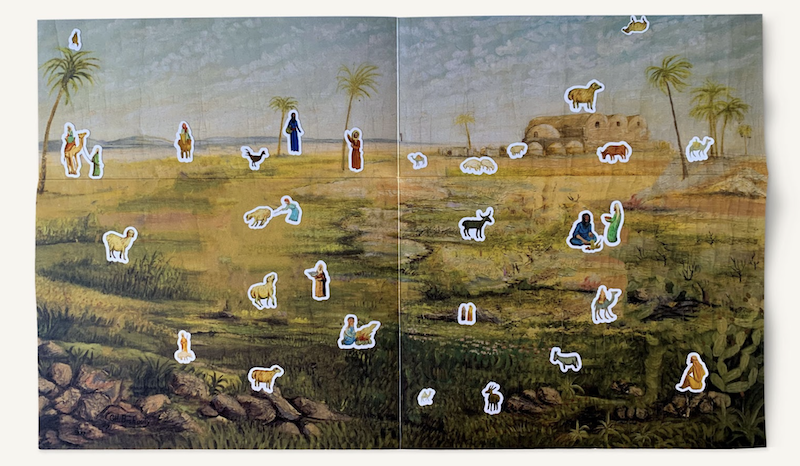

Nour Bishouty, Untitled (2022), inkjet print with die-cut stickers from the exhibition: Nothing is lost except nothing at all except what is not had by Nour Bishouty, February 3 to March 5, 2022, Gallery 44: Center for Contemporary Photography, Toronto, Canada. (Photo credit: Darren Rigo)

Nour Bishouty’s heritage is one of diaspora and displacement.

Her father, artist Ghassan Bishouty, was born in Palestine in 1941. At 7 he and his family fled to Lebanon, caught up in the Nakba – “the disaster.” Thirty years later the Lebanese Civil War displaced them again, and Nour’s family settled in Jordan, where she was born in 1986.

She now lives in Toronto, mostly by accident: A Palestinian-Lebanese-Jordanian artist in Canada.

With uprootedness and disruption central to Nour’s experience, she gravitates to both in her art.

Thus, she up-ends conventional art and installation practices with Nothing is lost except nothing at all except what is not had, her recent exhibition based entirely on Al-Wadi, a landscape painting by her father. In her show, she hangs framed works, their imagery obfuscated and askew, at random heights. She incorporates label-like wall text, off-center and hung nowhere near works a label might describe. A scientific-looking drawing is alone on a wall, ostensibly cataloging flora but including partly invented plants, the product not of clinical observation but rather the artist’s imagination. Even the complex syntax of the exhibition’s title disrupts expected norms.

Photo credit: Darren Rigo

Nour takes widely accepted exhibition-making practices and scrambles them, foiling our expectation of a staid and whole narrative presentation. Which makes sense, for Al-Wadi’s story is neither staid nor whole. In its fanciful portrayal of a picturesque Bedouin landscape, the painting itself is perfumed in nostalgia, evoking themes of separation and loss. Those themes are only amplified by the work’s provenance as an object, traveling place to place with its maker and his daughter, like a fragment from a lost world.

By not adopting wholecloth any single conventional system for making and presenting work, Nour is highlighting fracture and gap, the spirit of Al-Wadi, the wellspring for the exhibition.

The painting itself appears twice, each time in altered form: first near the entrance, where viewers can play the game of placing figures from the original painting on a digitally depopulated reproduction; second, within a large display table, whose glass top is etched with a grid and superimposed with (among other things) ostensible cartography symbols.

The rest of the installation is similarly layered and complex. Photographs (some framed, some pinned) offer fragmented realist counterpoints to the stylized Bedouin world of her father’s painting. Odd-shaped tables in the center of one room display wooden likenesses of desert cattle and camels from the painted scene, elongated and distorted. The pale blue sky and warm sienna sands of the painting step off the canvas and onto the gallery walls as bands of color. It’s as if Al-Wadi has undergone some kind of thorough autopsy, or perhaps been blasted into bits, parts scattered, defying established mechanisms of order.

Everything has wandered from its original home, resistant to ossified classification and systems – especially Western ones.

Photo credit: Darren Rigo

Which brings us to a seemingly small element of the show – the map pins.

These simple tools (a staple of Western geocoding) are typically used on maps to pinpoint locations – to orient us. They’re also a useful way to pin paper to a wall, and a common sight in art exhibitions: tidy rows of uniform pins in the corners of works, all in a line.

That’s not how Nour uses them.

In the photo on the right above, we see the pins are plentiful, showing up here and there, helter-skelter, like tossed darts. Some settle on paper images or text in random fashion, while others miss targets altogether, pinning nothing but themselves to the wall.

Which actually leads us to the point.

The exhibition catalog describes Al-Wadi as having been created “in a somewhat orientalist style.” “Orientalism” is an excellent word through which to consider the exhibition, for it not only evokes the historical baggage of the oppressive Western gaze challenged by Nour’s persistent subversions, it also brings to mind a different word: “orientation.”

As with many other elements in the exhibition, Nour’s use of map pins denies their customary purpose: she does not deploy them solely to pin something down, orienting the viewer. Map pins in Nour’s hands become a symbol of resistance.

In her installation, we see several standalone pins of red, blue, and yellow. Like an accident, they are startling, landing where they will. They have become metaphors – like wanderers, free-floating.

Like diaspora. Like Al-Wadi.

Nour Bishouty is a multidisciplinary artist working in a range of media including works on paper, digital images, sculpture, video, and writing.