They multiply, these cities of the heart,

these rooms we lodge our bodies in.

– from “Altogether Elsewhere,” by Tess Taylor

When on a run one day in 1995 I passed a blue and yellow O’Connor, Piper & Flynn real estate sign (ubiquitous then in Baltimore) and had a simple yet profoundly liberating thought: I wanted to make a drawing using those colors.

It seems hardly an earth-shattering notion, but for me at that moment, it was.

A decade before, in graduate school, I had started making art exclusively based on self-portraiture. At first I had sought verisimilitude, then the undertaking became conceptual, an ongoing exploration of all the ways a “self” might manifest. The one constant for all that time: looking in the mirror as my point of departure.

As the child of divorce, shuttling from house to house, I had constantly performed different identities, never really discovering who I was. As a young adult, spurred by this abiding sense of feeling out of touch with me, I began my self-portrait work. I was seeking my “true” self, an undertaking excluding anything not me: environment, place, home. (Identity for me then had to exist apart from all of that.)

This approach went on for years. Though it was rewarding and led to a rich run of art making, it carried with it an accompanying feeling of exile. Without any sense of rootedness in place, I had come to identify as a sort of spiritual refugee, feeling existentially alone and perpetually adrift. I had my family and felt loved but, untethered from any deeply felt centering from ancestry or home, I saw myself as perpetually belonging nowhere. This was reflected in my art.

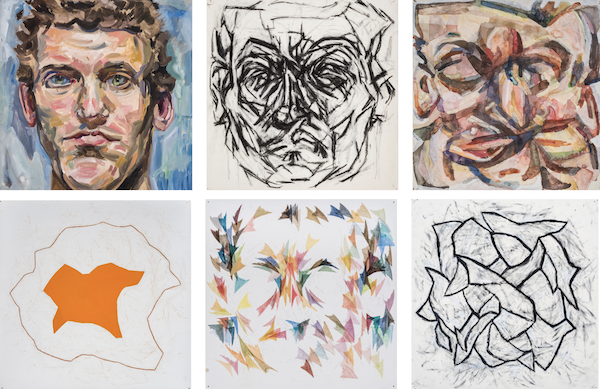

Images left to right, top to bottom: Self-Portrait #12, 1988, oil on canvas, 22″ x 22″; Abstract Head (Self-Portrait) #49, 1990, charcoal on paper, 22″ x 22″; Abstract Head (Self-Portrait) #168, 1993, watercolor on paper, 8″ x 8″; No Title #171, 2012, watercolor & pencil on paper, 9″ x 9″; Abstract Head (Self-Portrait) #44, 1994, charcoal on paper, 22″ x 22″

Just days before my run, my sense of homelessness had been freshly activated by the trip I’d just taken to visit museums and cathedrals in Europe; a feeling like envy had haunted me throughout. Everything I saw – all the artists I came across – were deeply imbued with what I was so aware of missing: a strong identification with place.

In France, from Sainte Chapelle to Matisse, the work was so grounded in French-ness (such delight in color, decorative and spry). In the Netherlands, artists from Memling to Mondrian were faithful to their homeland’s proclivity to organize and compartmentalize (the countryside all well-lined canals and tidy hedgerows). In Germany, from the Middle Ages to Dürer and beyond, so much was brute and austere (so very German). These artists – their authentic selves – weren’t separate from place but instead steeped in it, even defined by it.

I’d never had that experience, and was reminded constantly of my disconcerting rootlessness. But I could not conceive another way to frame things.

Until my last day in Europe.

That day, I visited a Francesco Clemente exhibition in Paris’ Pompidou Center. The artist is Italian, but his art is not – he courted influences of all kinds.Though not rooted to any one place, his art invited so much in: India’s spiritual sensuousness, America’s cocky confidence, Europe’s deep traditions. In Clemente’s globetrotting appetite I saw someone neither as locked in to identification with any one place, nor as homeless. I saw a nomad, and that idea was a revelation: unbound from any one place, I need not consider myself homeless. I could embrace nomadism.

Swirling with the notion of redefining myself as nomadic, I went for that run, wondering at the implications for me and my art.

I cruised by that realty sign and had my simple thought: I want to make a drawing with the colors of that sign.

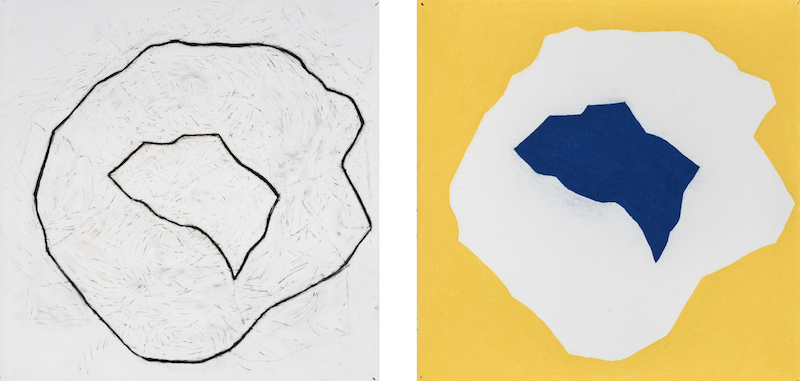

And so I did – not by looking in the mirror trying to expunge all external context, but rather by inviting outside influence (the colors of the sign). With whimsy and joy, I made the drawing above on the right, a variation of the one to its left, made just that morning the same way I always had. I was no longer in self-imposed exile from my surroundings, and the world was now my playground.

I had stopped believing I belonged nowhere, and realized I could belong anywhere.

I am a nomad, as are we all, and the world is ours.

Header images, left to right: Abstract Head (Self-Portrait), 1995, charcoal on paper, 22″ x 22″; O’Connor, Piper & Flynn, 1995, pastel on paper, 22″ x 22″