I didn’t want to sell it, but I ended up doing so.

As mentioned elsewhere in this issue, earlier this month I spoke at a conference in Florida where I shared my story to illustrate the impact of addiction, reminding the hundreds of medical practitioners assembled of the importance of their work, my grieving over my daughter’s death from an overdose in 2014 a case study in consequences.

I spoke of her, I spoke of my art, and I spoke of love.

After I concluded my remarks, it was announced I would be available in the lobby with a selection of my art on display – and for sale.

That was an error: I had neither the intention nor wish to sell my work.

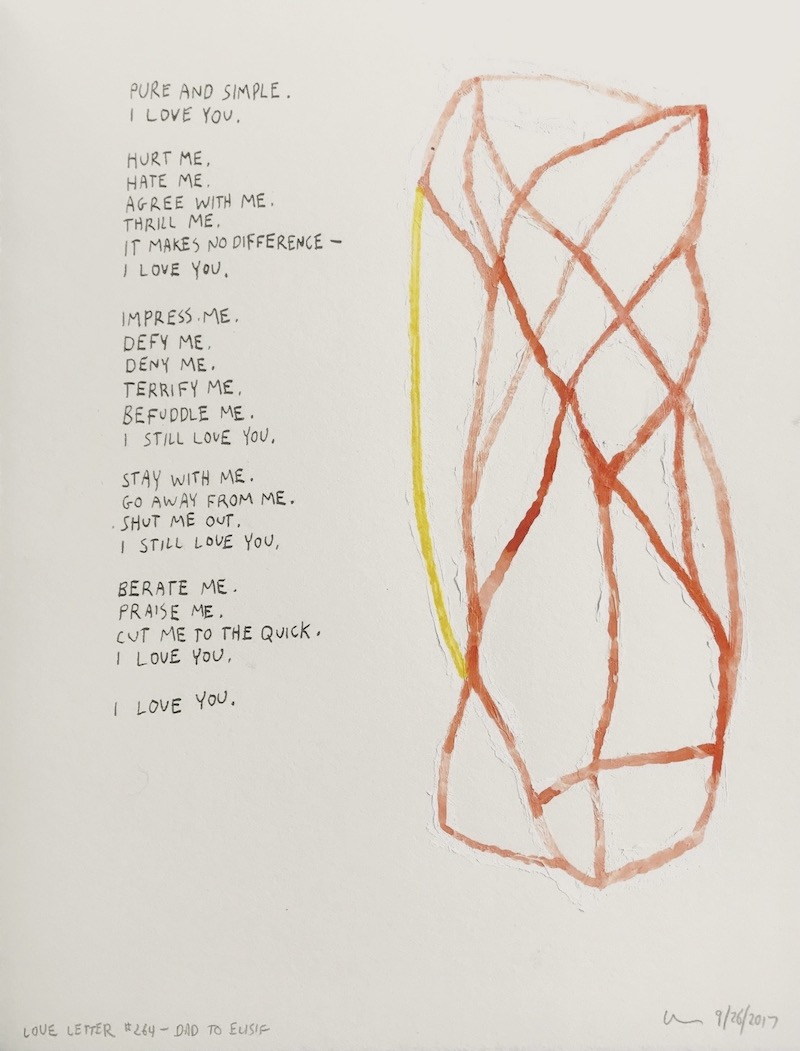

Nonetheless, I took up position by a dozen drawings from Beyond Beautiful: One Thousand Love Letters – 10 drawings inspired by condolence letters following Elisif’s death, and two based on words from me for Elisif.

At best, I have always felt ambivalent about selling my art. On the one hand, art’s meaning and resonance can be augmented when placed in someone’s home, and if a person likes my work, it’s wonderful if they can have it. On the other hand, I am attached to my art, and philosophically resistant to breaking up the body of works I make, individual pieces becoming like so many leaves scattered in the world.

Selling art comes with being an artist, yet I resist it, especially with works as excruciatingly personal as these particular love letter drawings I elected to share at the conference – most especially the one illustrating the top of this article.

So there I was, by my display, feeling flustered and vulnerable, fending off several inquiries about buys with equivocations about visiting my website’s sales gallery. Everyone was understanding, and I got away unscathed, happily not having sold a thing.

I then checked my email:

“I’d like to purchase the framed letter with the poem that states ‘love me…, deny me…’”

My immediate impulse was to reply with a polite decline. But first, I Googled the prospective buyer and discovered the principle of love is central to her addiction medicine practice.

Maybe I would sell this drawing to this person – maybe she was exactly who should have it.

So I did.

We then had a correspondence, me writing her first:

“A note about the image. I was thinking about a body (her body) as a kind of standing column, struts holding it together, it falling (weakening) on a side (the side with yellow), me (my love) like a band, trying to suspend it all together – keep it from collapse. I also was thinking about Michelangelo’s final Pietà (in Milan), where from one angle (head on) Mary and Jesus appear to be melting in collapse, and from the side view, Mary’s back is taut as a bow, holding, holding, holding. That’s me: the bent yellow.”

She answered:

“Thank you so much for sharing – I am haunted by the faces of my patients that have died.”

I replied:

“You and I share burdens, which we could not bear (I am sure) were it not for the love we carry too. I am honored (so honored) to have this connection, and in part through the drawing you now own. It could not be in more fitting hands.”

She agreed she would send me a photo of the drawing once she’d had it framed and hung in her office, and that was that.

Though not really, for some aura lingers in the wake of this exchange… a sense of bond in survivorship. Of fellowship in pain and grit. Of love.

All because I sold a drawing.