I was recently invited to Florida to open the annual conference of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) with “my story” – aspects of which many of you are familiar with, for I often share about it publicly. My job at the conference was to complement the medical conversations with a dose of heart and humanism. I was glad for the opportunity on many levels. For one thing, I haven’t often had a chance to express my gratitude for the work of health providers in this field; additionally, this context allowed me to demonstrate how critical art is to survival, both for me and for others I’ve worked with. For this month’s Prologue, I am sharing a transcript of the speech (edited slightly for format) in the hopes that doing so offers insight on how we might look upon and treat those affected by addiction, and also a glimpse of what pushes me to make art with urgency.

– Peter

I began working on my remarks for today on February 11 of this year, the 8th anniversary of my daughter – Elisif – dying from an overdose. Thinking about her in some organized way felt the right thing to do that day. I set the mood by lighting candles in my home and playing Amy Winehouse on Spotify. And – of course – I cried.

I want to talk about damage.

Not so much the damage you in your practices see every day – the lying, stealing, cheating, evading and denying that comes with substance use disorder – the damage SUD wreaks upon families and loved ones, our children’s hearts and minds co-opted by addiction’s drive to thrive with use and use and use.

Not that damage. That’s a damage everyone in this room is familiar with. No – you see, from my perspective, that damage is prelude.

I’m about to play something for you, but before I do, let me say at this point that I am an artist.

I mention that now in part to contextualize this bit of audio I’m about to share. But also I want to make clear up front that my survival – my recovery back to life in the wake of my daughter’s death– I fully credit to being an artist. Art has allowed me to go into the abyss of losing my daughter to addiction – as an artist, I’ve tried to leave no pain unexamined – for I believe love and pain go hand-in-hand through the same door, so for me, retaining the love means walking the pain… nurturing my grief through art… bearing witness and testifying to addiction’s consequences – it’s impact on me, it’s affect on others – all its damage… for without having excavated it, I do not believe I could have come out the other side as I have.

For that, I count myself lucky.

So right away after Elisif died, I began processing my grief by working on an art project about her. Part of making it meant recording interviews with those who had known her – I cut and pasted their voices together to create the arc of a story – Elisif’s Story. What I have for you today is a smattering of that audio – I’ve put it in video form.

[click here for video segment]

The damage from Elisif’s passing ripples far out beyond just her, or just me – her dad.

There is wide breadth to the damage.

And there is depth.

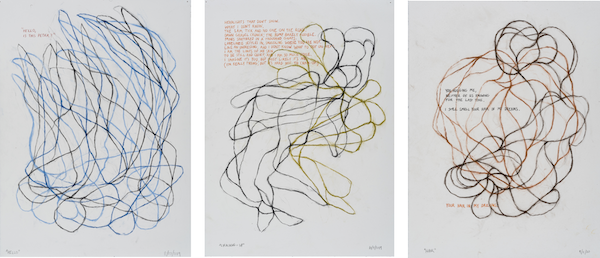

These three drawings are from a series of dozens I made two or three years ago that I think of as memoir drawings. The left drawing represents the line between before and after. On it, I’ve written the words that changed my life:

“Hello, is this Peter?”

That phone call. Your first born is dead. What comes next is falling.

The drawing on the right:

“You hugging me, neither of us knowing for the last time. I still smell your hair in my dreams. Your hair in my dreams.”

The middle drawing:

“Headlights that don’t show.

What I don’t know.

The 1AM tick and no one on the road.

Dawn gravel crunch, the bump barely audible.

Panes smattered in a thousand gnats.

Loneliness settles in, snuggling where you are not.

Like an undressing, and I don’t know what to put on next.

I am the limits of my skin.

To be still and quiet, and I am so much noise.

I imagine it’s you but most likely it’s not.

(I’m really trying, but it’s hard not to crack up.)”

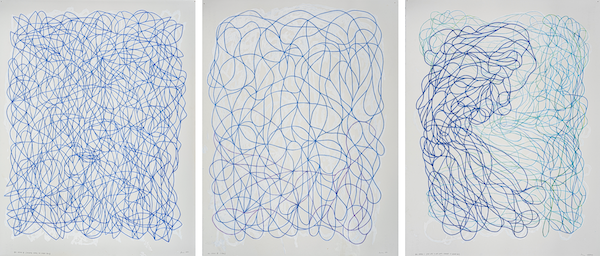

These are three from another series I call Big Crying, for in these years since my daughter died I have cried so much.

I have cried from the hard dreams I still have at night. From the recurring anxiety and depression that comes with each anniversary of her death, each birthday she’s not here. From her absence at her sister’s wedding this past summer – her absence at every family occasion.

I have also cried tears of gratitude – for I have come to know and understand love as I never had before; love, the one thing that does not die. The love of Elisif’s story: so full of tears.

Here’s the rub: there is nothing – nothing – special about my daughter.

560,098 children of parents have died in the U.S. of overdose since Elisif died.

Each is an Elisif, and the damage is immense.

Most if not all of you in this room work as healers for those with addiction. I know you care, I know you know and feel the harm and pain that attends SUD. You know damage too.

I also know – because I have lived it – the behaviors that come with addiction are confounding. It is exhausting and wearing and at worst it can cultivate diminished empathy between you and your patient – that too can be part of the damage, as it was with Elisif and me and her family while she was still alive. That did not help.

Which is in part why I am here today: to remind you – to bring home anew – the truth of the humanity of those you work with as healers.

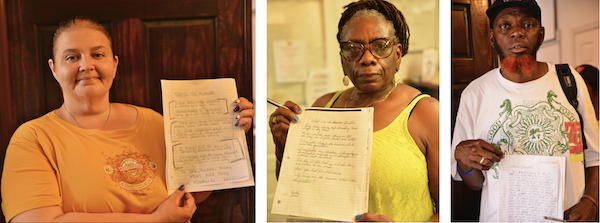

These photographs are from a project I did several years ago in partnership with Johns Hopkins Medical Center called The Road to Recovery Is Paved with Love – for me part of a larger project called Beyond Beautiful: 1,000 Love Letters. For the Hopkins project, we held a series of love letter writing workshops at treatment and recovery programs. I then made drawings inspired by those love letters, the point being to uncover the emotional life of those living with SUD even as in their affect it seemed entirely absent.

Heather writes in her letter, to mom and dad:

“Each day that passes I miss you all so.”

Veda’s letter: “I neglected my children I do apologize.”

Charles, in a letter to himself:

“It’s really good to finally meet you. I’ve been in love with you a long time, but never said anything, because I saw you were in love with someone else. I hated to see you so used and abused by a love that could never be true.”

Addiction.

It is as pernicious and perilous in divorcing those who suffer from it from their humanity as it is on us. We too can be numbed from its assault on our hearts.

The point of The Road to Recovery is Paved with Love and the point of my sharing with you today is to remind you how much what you do and how you do it matters.

Each encounter with a patient. Each moment of listening carefully. Each kind word. Each prescribed course of action. Each gesture of love toward your patient – each is like a pebble tossed in a pond, sending out ripples of perhaps immense consequence.

Your work is the difference.

Your caring is the difference.

You are immense.

I close by asking you to remember the only thing between another 560,098 dads in happy joy with their families and the same number of dads alone and in grief might very well be your pebbles in the pond.

Photos of artwork by Dan Meyers; photos of Heather, Veda, and Charles by Ken Royster