This is the eternal origin of art: That a human being confronts a form that wants to become a work through them. Not a figment of their soul but something that appears to the soul and demands the soul’s creative power.

– Martin Buber

My bedroom is cool, the window open to the spring air. Outside, the insects and peepers are silent; the hum of a fan in the crawl space above, barely audible, is the only sound.

That, and my fingers tapping on my iPad screen.

I have insomnia.

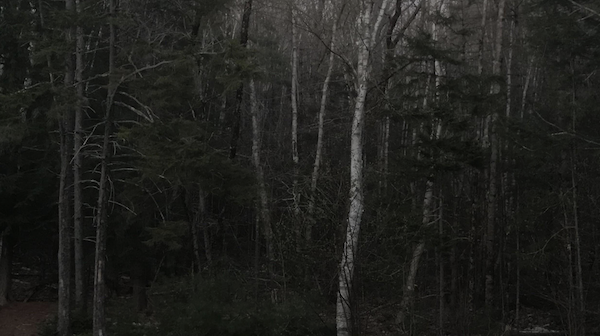

It’s dark. There’s no moon tonight, and as the bedroom faces the forest, there are no cars or neighborhood lights.

Just woods.

And I am awake.

I was talking recently about art as my steady companion, how through times of grief and confusion I can always rely on it, helping me through like a faithful partner. Words can be that way for me too: like syrup and song, sweet.

(A distant bird’s warbling momentarily breaks the midnight hush.)

Earlier in the day, I was asked to be an expert – to judge art. My task (along with two other jurors) was to single out a pair of artists among 12 to be recognized for the merit of their work. We complied with the assignment, spending time in the gallery with our measuring eyes.

The job made me more uncomfortable than I expected; lying awake with this weighing on my mind, I turned to words.

I am writing as a confession: today, I stumbled into betraying my belief in art.

I do not believe in evaluating art’s merit; though we act as if merit is a thing that matters with art, it does not. Art is not made to be meritorious – it exists because of urgency, to meet that “something that appears to the soul and demands the soul’s creative power.”

I abhor judgment toward art, and I judged today – that is my confession.

(In the gloom, an owl’s hoot rises, and then falls.)

*****

I dream of Elisif again.

In the dream, she is an adult, reckless and indifferent, arrogant and in peril; the atmosphere is sickening. I want to wake, and I do, only to doze off again and pick up right where I left off.

“I’ve made up my mind. Nothing you do or say will change that.”

Too real. Too hard. I sit up.

I recall the day Elisif died. That very day, drawings came to me, ready-formed in my head.

(“This is the eternal origin of art: That a human being confronts a form that wants to become a work through them.”)

I made them, of course.

Nearly two years later came the exhibition Elisif’s Story: recorded voices knit together in a quilt of a tale filling the gallery, dim lights rising and falling, washing across those same drawings.

Like salve and psalm, holy and unbidden as my haunting dreams, art rises from a place of mystery, “merit” and “expertise” irrelevant.

(A loon cries its aching song, a companion in the night.)