What Duchamp Teaches Us

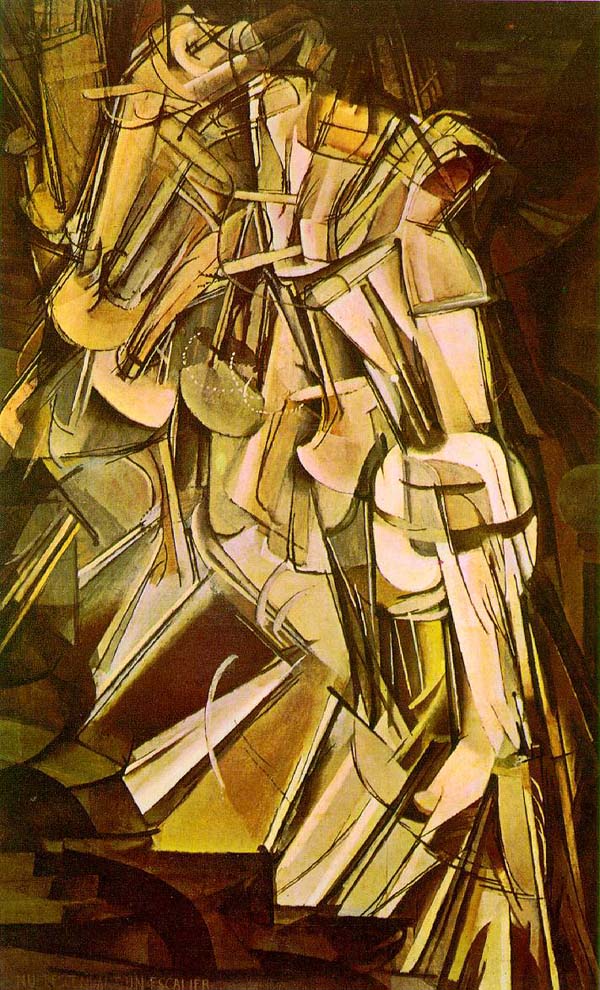

“On March 18, 1912, Marcel Duchamp received an unexpected visit from his two brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon… They informed their younger brother that the hanging committee of the Salon des Indépendants exhibition in Paris… had rejected Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. These Cubist painters had refused to display the painting on the grounds that ‘A nude never descends the stairs—a nude reclines.’”

(Philadelphia Museum of Art, wall label)

*****

What might we make today of this rich art historical moment?

Let’s enter that question by digging a little further into the Duchamp tale:

Cubism was celebrated in its day by progressive thinkers as liberating—art was freed from the constraints of slavish fidelity to the appearance of things. Duchamp bought into that notion of liberation, taking it farther than his peers… so far, in fact, that in leaving them behind his vision became perceived as a threat to theirs; ergo, the rejection of Nude Descending A Staircase, No. 2.

The irony was not lost upon Duchamp; it fueled him. Fountain—the famed urinal he turned on its side, signed “R. Mutt 1917”, and submitted to another supposedly open-minded exhibition committee in New York City only to have it rejected—dives directly into the hypocritical foibles of human nature: ostensibly free thinking people are not as free thinking as they think.

(Upon the anticipated refusal to include his work in a supposedly open exhibition, Duchamp wrote a letter to the committee challenging the rationality of their decision and famously positing the notion that artistry is more a function of choice than making—and thus Conceptual Art was born.)

So—what are we to make of this rich historical moment today?

In recent months, I have found myself deeply involved in matters related to equity, particularly regarding access to the arts. There are those among us (myself included) who decry the inequity we are part of—the unequal access to resources, the absence of certain groups from decision-making tables—while at the same time being so immersed in our own soup that we are blind to our own complicity in perpetuating the situation: when push comes to shove, we are not as free thinking as we like to think we are. In some ways, we are no more enlightened than the Cubists who refused Duchamp’s art.

In knowing and remembering this, I perhaps stand a chance of correcting my actions moving forward; I can perhaps behave less laughably than those who gave absurd reasons for not showing Nude Descending A Staircase, No. 2 or Fountain.

But the moral of the story is not only about not acting badly; the more important lesson to glean is I stand to gain by letting go and letting in. Remember: those who eventually clued into what Duchamp’s art is about discovered an entirely new and expansive notion of art—their worlds became larger, just as yours and mine might if we summon the courage to question our convictions, surrender our preconceptions, and give space to other voices and other ways.

Easier said than done, but worth the doing.