Welcome! For the best viewing experience of Grace, please visit this site on a desktop or laptop.

Grace. Unmerited mercy. Goodness granted despite all. The lost restored in new fullness. Art has that power: the power to deliver grace—to be a kind of prayer and answer all at once. So it is for Peter and six others featured in this online exhibition—artists for whom grace emerges as a wondrous gift, for them and their audience alike.

PART I

This section of Grace features art by Peter—five thematically resonant works he has chosen to share for this online exhibition.

The concept of grace, in all its variety and nuance, touches each of us differently. Peter both seeks and expresses it through his artwork, which bespeaks the immeasurable impact of family death, and the enduring capacity of love to defy the boundaries created by such loss. In his art, these contrary elements of pain and joy from time to time merge in moments of grace.

We Are Five stands as an example. The use of “we” in this work’s title has to do with Peter’s family, but it also stands (in my mind) for the value Peter places on the families, communities, and gatherings we make for ourselves—like the grouping of artists whose works he has selected for this exhibition.

Together, the artists and their works in Grace convey the essential importance of acknowledging our vulnerability and discovering our gratitude. By sharing his art and curating this exhibition, Peter offers us the opportunity to join him in pursuit and praise of grace.

—KATHY O’DELL

Kathy O’Dell is an art critic and art historian, Associate Professor of Art History and Museum Studies and the Special Assistant to the Dean for Education & Arts Partnerships at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

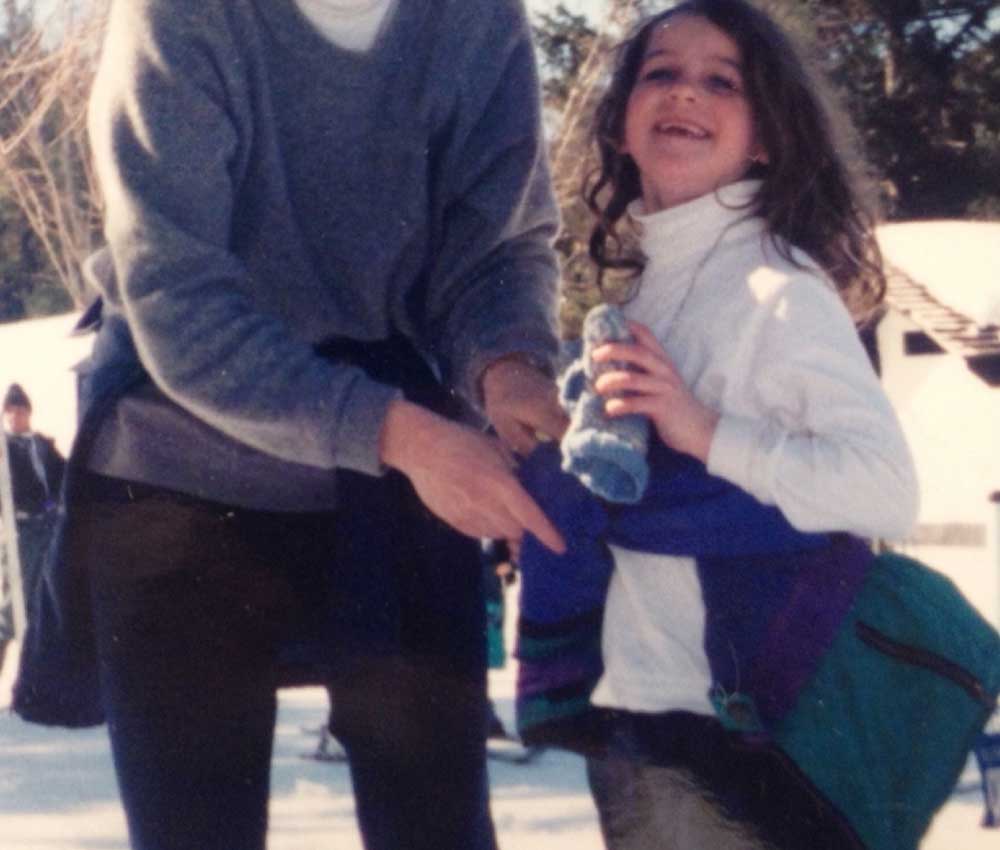

Dad Reckoning with a child’s mortality, and a parent’s helplessness.

Peter Bruun

1996, 30”x30”, oil on linen

She was 6 years old, and something was very wrong.

On a family ski trip in the winter of 1995, Peter’s daughter Lis was constantly thirsty and had to pee all the time. A worried call to the family pediatrician and immediate urine test delivered a dreaded diagnosis: Lis had developed Type I diabetes, a lifelong and potentially fatal disease.

Inconceivably, the shadow of mortality had fallen on Peter’s bright spark of a daughter, and he was helpless to prevent it.

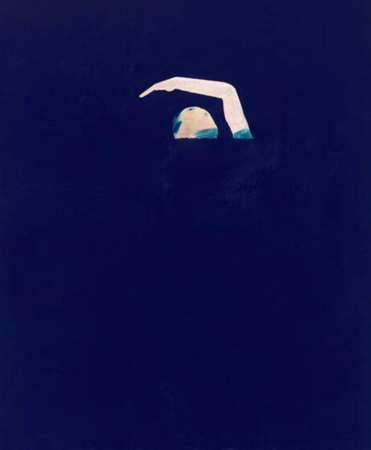

After the crisis subsided, Peter returned to the studio and found himself frustrated, unable to resolve the painting he’d been working on.

One day, getting nowhere, Peter recalled an anecdote about contemporary artist Robert Moskowitz.

The story went that in a moment of desperation while working on a new painting, the artist seized a jar of Prussian Blue pigment and covered the confounding canvas with it. As he layered it on, he discovered how to resolve the painting; the result was his landmark work, The Swimmer.

Inspired, Peter coated his over-worked painting in Payne’s Gray. Beneath the semi-translucent veneer, hints of color poked through.

From there, it was just a matter of pulling out the color from within the darkness.

From there, it was just a matter of pulling out the color from within the darkness.

Vivid colors shone like a prayer answered: a painting solved, a gift of meaning for a frightened father. That meaning: Though shadows fall, though illusions of our children’s immortality shatter, color and life remain, twinkling as gems in a mine.

Vivid colors shone like a prayer answered: a painting solved, a gift of meaning for a frightened father.

That meaning:

Though shadows fall, though illusions of our children’s immortality shatter, color and life remain, twinkling as gems in a mine.

Gifts from the dark: grace granted.

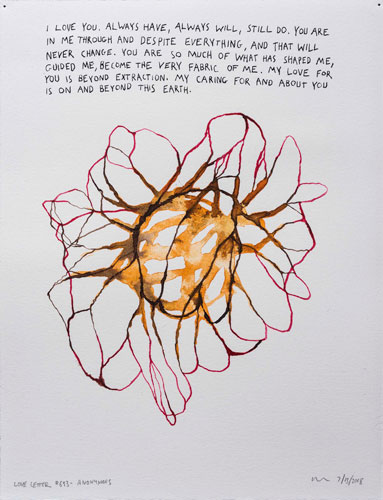

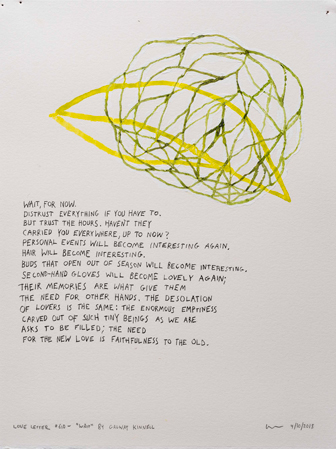

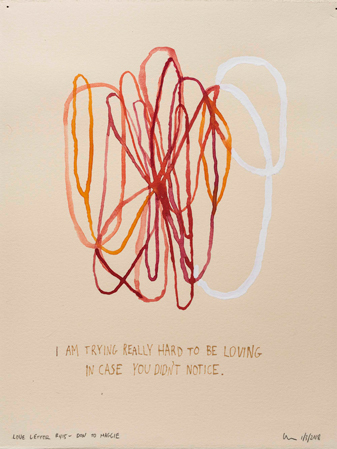

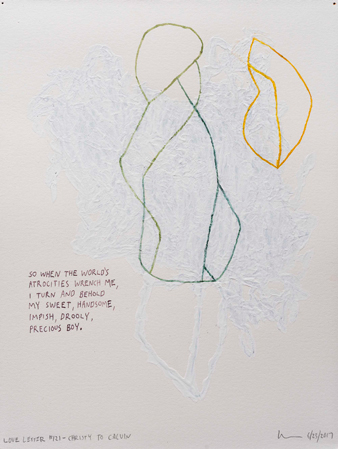

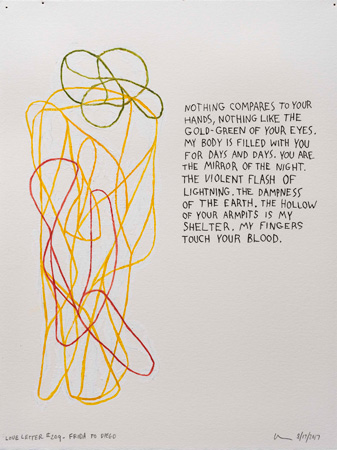

Love Letter #693 Illuminating love’s truth even when life prevents its manifestation.

Peter Bruun

2018, 8.5”x11”, ink on paper

This is a kind of love story.

Once upon a time…

A Palestinian artist, Jasem Shuman, participated in an exhibition Peter organized in 2010 while he was cultural envoy to Israel for the U.S. State Department.

At the show’s opening in Jasem’s hometown of Ramallah, he met a woman—a fellow artist from East Jerusalem—and the two fell in love.

But standing between them and a life together was the Israeli West Bank barrier, built by Israel along the Green Line and barring Palestinians from easily crossing back and forth. The physical blockade reverberated into family politics and daily life, ultimately making being together impossible.

Seeing no way forward, they moved on to wed others and live separate lives.

Yet their love persisted in Jasem’s heart, undiminished by life’s circumstances.

Jasem made a painting about it: 20 Centimeters.

With a gap symbolic of the physical wall between the lovers, the diptych nonetheless depicts a single image: their two names in Arabic, visually joined across the barrier.

Two bodies, and one soul.

Peter reconnected with Jasem in 2020 and learned this story, seeing in it an echo of his own life. He too had made art about such unattainable love.

For the two-year project Beyond Beautiful: One Thousand Love Letters, Peter made drawings inspired by hundreds of actual love letters. The letters were between all sorts of people, sharing stories of all kinds of love. A few were Peter’s own.

For the two-year project Beyond Beautiful: One Thousand Love Letters, Peter made drawings inspired by hundreds of actual love letters. The letters were between all sorts of people, sharing stories of all kinds of love. A few were Peter’s own.

The story behind Love Letter #693 is one of those. Just like Jasem’s, a tale of deeply felt love out of reach, but eternal in Peter’s heart.

For both men, impossible love embodied through the grace of art.

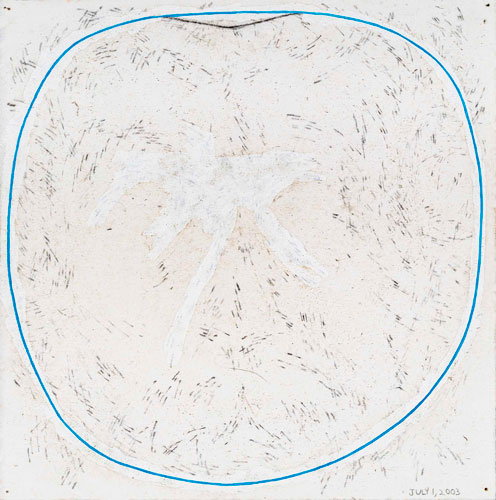

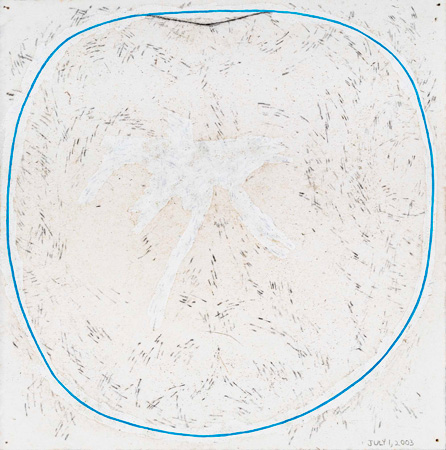

No Title (July 1, 2003) Finding solace after a loved one’s sudden, unexpected death.

Peter Bruun

2003, 8”x8”, gesso, gouache & charcoal on paper

“J. Player Crosby, 61, of 137 Jerusalem Road died Thursday of an apparent heart attack as he was flying his single-engine airplane.”

So begins The Berkshire Eagle’s obituary for Peter’s step-father.

His death on June 19, 2003, was as shocking as it was devastating. Young, fit, and in seemingly perfect health, such a fate seemed inconceivable for Player. Family and friends gathered for days, gripped by grief.

No Title (July 1, 2003), Peter Bruun, 2003, 8”x8”, gesso, gouache & charcoal on paper

In the immediate aftermath of Player’s passing, Peter found time alone each day to draw. He ended up making nine drawings—a series of works born of anguish, marking his sadness.

No Title (July 2, 2003), Peter Bruun, 2003, 8”x8”, gesso, gouache & charcoal on paper

In the immediate aftermath of Player’s passing, Peter found time alone each day to draw. He ended up making nine drawings—a series of works born of anguish, marking his sadness.

No Title (June 27, 2003), Peter Bruun, 2003, 8”x8”, gesso, gouache & charcoal on paper

In the immediate aftermath of Player’s passing, Peter found time alone each day to draw. He ended up making nine drawings—a series of works born of anguish, marking his sadness.

As he drew he was influenced by a bit of art history: A Mesoamerican burial rite in which perfect ceramic burial containers were intentionally pierced, perhaps to allow the spirit of the deceased to escape, perhaps to symbolize the uselessness of the broken vessel.

In each piece, Peter drew an idiosyncratic cerulean blue shape, its perfect roundness interrupted by a rupture—a caesura; an opening. Bits of erased charcoal marks flake the paper; gesso-white paint stands in cool contrast to the cream-colored paper’s warmth.

Caesura: an internal flaw/an artery blocked

Opening: container broken/spirit’s exit

Color: ghostly whispering white/divine heavenly blue

Through drawing, a loved one’s passing named, his soul’s release accepted.

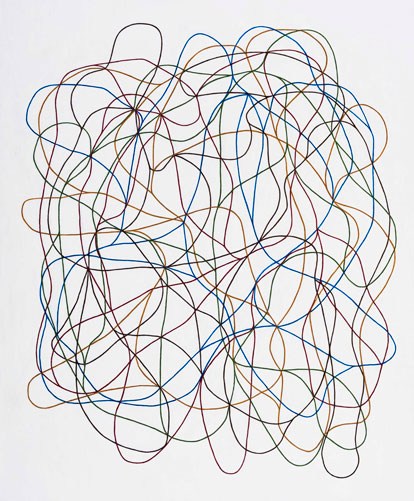

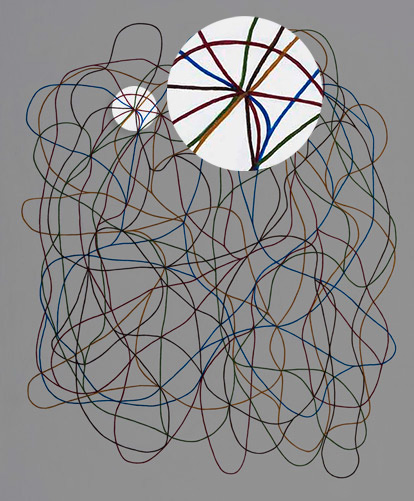

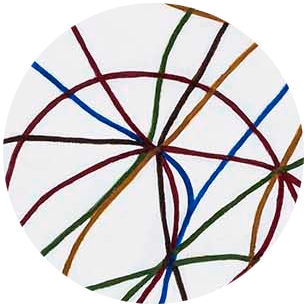

We Are Five Through the grace of art, Peter’s faith in his family’s eternal bond is unexpectedly affirmed.

Peter Bruun

2019-2020, 20” x 24”, oil on panel

At the memorial service for his daughter Elisif, Peter spoke of his family of five as immutable.

“We are five,” he said emphatically. “We are five.”

Years later, despite evidence to the contrary, that truth appeared unexpectedly in a painting; though unforeseen, it was not entirely surprising.

For in art, Peter knew, not all is as it first appears.

As an example, the Baroque masterpiece Guardroom with the Deliverance of Saint Peter ostensibly shows a secular subject—how prison guards pass their time at leisure—but more is at play. In the background just beneath the half-descended portcullis, in quiet reveal, Saint Peter is miraculously delivered by a savior angel.

How unexpected; what a gift for the keen observer.

And so too with We Are Five: A surprising moment hovers, as startling for the artist in this case as for any viewer.

Peter had not set out to paint this gift of a moment or its meaning, but it’s there—the natural product of the painting process.

And so too with We Are Five: A surprising moment hovers, as startling for the artist in this case as for any viewer.

Peter had not set out to paint this gift of a moment or its meaning, but it’s there—the natural product of the painting process.

Embedded in this story of wandering and apartness, a contrary story emerges.

Look closely…

See the particularly dense gathering of lines toward the upper left corner. At that one spot in the painting (and only there), all five colors—each standing for a family member—converge at a single point.

It is a revelatory moment—the denouement, where the painting’s narrative turns on its head, shifting from a tale of apartness to one of communion. From one story of “we are five” to another.

As easily unnoticed as the angel freeing St. Peter, it nonetheless is there.

Truth affirmed and delivered.

The proof of his immutable five, revealed through art’s grace.

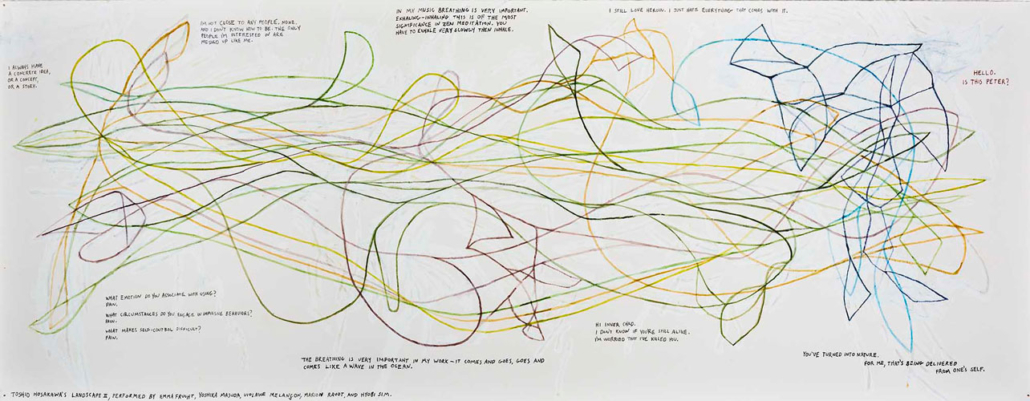

Hello, Is This Peter? The tale of a daughter’s trauma, and a father’s healing by the telling of it.

Peter Bruun

2017, 29.5” x 11.5”, ink, watercolor, gouache, pencil on paper

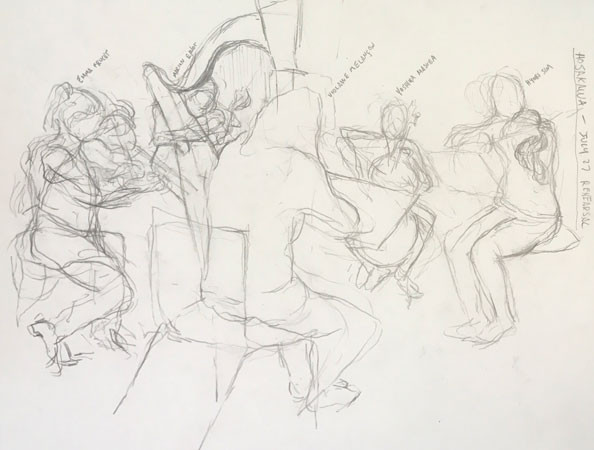

In summer 2017, Peter spent three weeks as resident artist at the Yellow Barn Music Festival in Putney, Vermont.

Sketch by Peter Bruun of Yellow Barn musicians rehearsing Landscape II.

During that time he sat in on rehearsals, sketching the musicians as they worked on chamber pieces to be performed later in the summer.

In one such session, Peter heard Toshio Hosokawa’s Landscape II for the first time.

Unexpectedly, the emotional energy of the piece brought to mind his daughter’s journey through addiction to death.

Inspired directly by Landscape II and playing the piece over and over again, he made the drawing Hello, Is This Peter?

Hello, Is This Peter?, Peter Bruun, 2017, 29.5” x 11.5”, ink, watercolor, gouache, pencil on paper

In the drawing, Peter echoes aspects of Japanese scroll painting: open space and horizontal flow in contemplative calm. In Japanese scrolls, the poets’ words written in black are answered by the collectors’ red stamped marks; in Peter’s piece, his daughter’s unsettling journal excerpts in pencil reverberate in counterpoint to the composer’s meditations in black ink.

Peter revisited the trauma of his daughter’s death while making the drawing. Echoing the musical piece, it delivers a truth: that we humans are fully subject to nature’s ebb and flow, connected to forces larger than ourselves.

In that, Peter found acceptance—a healing—a kind of grace.

PART II

On June 26, 2015, President Barack Obama sang Amazing Grace before a stunned congregation.

Years later, he explained that in that moment, at yet another eulogy for a victim of gun violence, words failed him; they no longer seemed enough.

At a loss, the gifted orator reached for music, and it delivered. As the simple, centuries-old strains of Amazing Grace filled the church, they first invoked and then delivered grace to the grieving.

The ability of art to deliver grace is an ancient truth.

In this section of Grace, six artists share their art, and in doing so unveil their experiences of grace. And just as the word carries so many nuances of meaning, so the concept weaves through the artists’ practices in varied ways, each bringing another shade of grace to light.

—PETER BRUUN

Peter Bruun is a Maine-based artist, writer, and curator.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Anastasio

DANIEL ANASTASIO

A classical pianist finds grace in one of the last pieces Franz Schubert ever composed.

Daniel introduces Franz Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-flat Major, and explains why for him the second movement, in particular, speaks of grace.

Daniel introduces Franz Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-flat Major, and explains why for him the second movement, in particular, speaks of grace.

Daniel performs Franz Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-flat Major, Movement II.

Daniel performs Franz Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-flat Major, Movement II.

ALONZO LAMONT

A playwright’s meditation on grace.

Originally intended as a written piece, Alonzo LaMont’s Grace appears here as a video—one created especially for this online exhibition. Rather than overtly defining or describing grace, Alonzo’s piece implies its presence: grace a kind of hovering, like aroma infusing our air, softening our hard knocks, as majestic as it is mysterious. —Peter Bruun

Grace. In two voices

Alonzo LaMont

4:51 single-channel video

Voiceover: Holly Morse-Ellington & Alonzo LaMont; Video Editing: Julia Golonka

Grace. In two voices

Alonzo LaMont

4:51 single-channel video

Voiceover: Holly Morse-Ellington & Alonzo LaMont; Video Editing: Julia Golonka

PHYLICIA GHEE

In her video 8:46, Phylicia Ghee delivers grace from a place of pain.

“8:46 is a visual prayer named for the approximate amount of time the officer kneeled on George Floyd’s neck ultimately killing him. This work is in honor of George Floyd and countless others.” So writes interdisciplinary artist and photographer Phylicia Ghee, whose practice—its inclusion of ritual and ceremony; its physicality—is grounded in art’s healing power and its promise of grace. Anchored by the continuous sound of Phylicia’s breathing, 8:46 shares moments from the artist’s life in layered and overlapping imagery—a montage of inherited and learned restorative healing practices. —Peter Bruun

8:46 visual prayer

Phylicia Ghee

9:32 single-channel video with sound

Voiceover: Phylicia Ghee

8:46 visual prayer

Phylicia Ghee

9:32 single-channel video with sound

Voiceover: Phylicia Ghee

Photo courtesy of circe dunnell

CIRCE DUNNELL

circe dunnell shows grace where there is suffering or hurt.

Few inequities fail to catch circe dunnell’s eye: how we abuse and neglect entire populations; the ways we leave people unseen and unheard. “As a child I pictured grace as something bestowed upon humans by a celestial being: God’s hand reaching out to give life to Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, for example,” says the artist. “As an adult I have come to recognize grace as the kindness that is offered to those who have struggled and perhaps fallen short, or to those whose actions have not garnered their due attention.” Through art, circe brings grace, and honors the grace of those all around us. —Peter Bruun

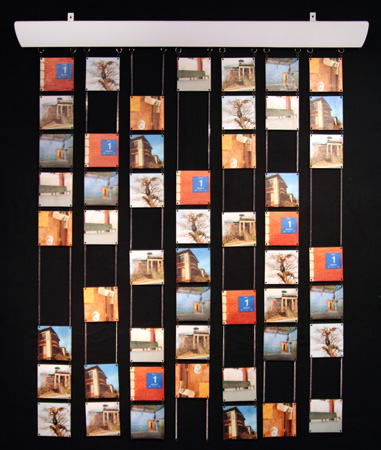

The Spaces that Remain; Overbrook Asylum—Closed

circe dunnell

2013, 24″ x 32″, mixed media: encaustic, paper, archival printing, metal findings

“Known as Overbrook, New Jersey‘s Essex County Asylum for the Insane closed in 2007. It remained unoccupied for years until part of the hospital grounds were reincarnated as parkland. “How we, as a society, care for those who are ill, aging, and or needy remains an inscrutable, and deeply disturbing, subject for me, and is the subject of this piece.” —circe dunnell The Spaces that Remain; Overbrook Asylum—Closed

circe dunnell

2013, 24″ x 32″, mixed media: encaustic, paper, archival printing, metal findings

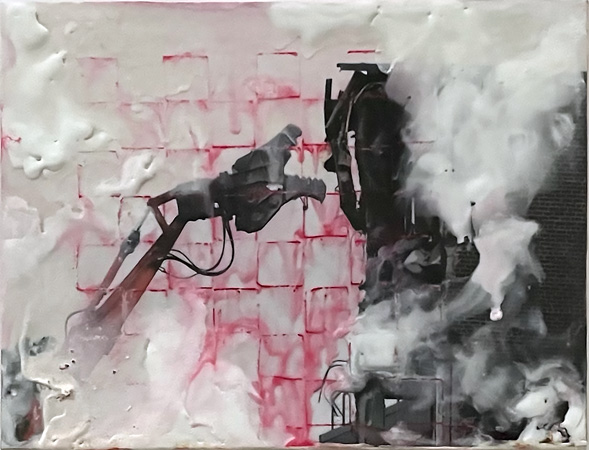

Ward 1

circe dunnell

2016, 8″ x 8″, mixed media: oil, encaustic, paper, archival printing

“How many in Overbrook’s Ward 1 cried, called out for help, or for forgiveness? Cried out in anger and resentment? Cried, asking for strength?” —circe dunnell Ward 1

circe dunnell

2016, 8″ x 8″, mixed media: oil, encaustic, paper, archival printing

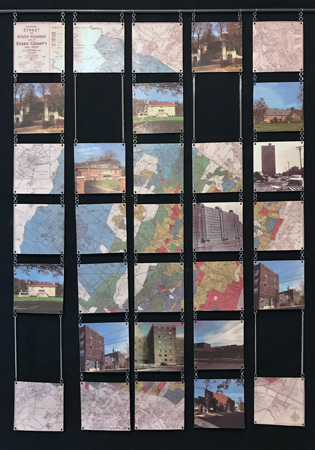

Duncan Projects, circe dunnell, 2011, 8″ x 6″, mixed media: encaustic, paper, archival printing

Duncan Projects

circe dunnell

2011, 8″ x 6″, mixed media: encaustic, paper, archival printing

“The Duncan Avenue housing complex, commonly known as Duncan Projects, consisted of high-rise buildings that were eventually torn down in 2011 to make way for low-rise buildings that studies indicated were less prone to crime. How many people were dislocated because some study showed that high-rises increased crime? Poverty, lack of means and education increases crime. On the other side of Jersey City from this location, high-rises inhabited by wealthy individuals appeared to show very low crime rates. This is how we treat those in need: our society tears them apart.” —circe dunnell

Essex County, NJ—1939

circe dunnell

2019, 22″ x 30″, mixed media: encaustic, paper, archival printing, metal findings

”Redlining—refusing to provide financial services to consumers (primarily people of color) based on the area where they live—has deep roots in privilege and power. Redlining increased poverty, adversely affected infrastructure and education, and cemented racial inequities in place. “I was shocked when I exhibited this work by how many white people told me they were unaware of redlining. Many do not know how far back in U.S. history individuals in power used these maps for their advantage. Ramifications of this now-illegal practice are still manifested in cities and towns across the U.S. today.” —circe dunnell Essex County, NJ—1939

circe dunnell

2019, 22″ x 30″, mixed media: encaustic, paper, archival printing, metal findings

Signs

circe dunnell

2019, 30″ x 42″, archival digital print

“Gender identity is the personal sense of one’s own gender, whether or not that corresponds with a person’s assigned gender at birth. Various states in the U.S. initiated laws to prevent individuals from using the bathroom that matched their (chosen) gender identity. No law seemed as egregious as North Carolina, where the state government attempted to in effect ban transgender people from using bathrooms in state buildings. It took public outcry and ultimately court action to overturn the discriminatory law.” —circe dunnell Signs

circe dunnell

2019, 30″ x 42″, archival digital print

“Grace is according dignity to every being, because that is the right or just action. If people could offer grace more generously and more often, perhaps the world would be a less painful place.”

—circe dunnell

ALEXY SANTOS

In making videos to illuminate his writing, Alexy Santos finds grace in a world otherwise overflowing with loss and doubt.

Alexy Santos creates more from need than choice. He writes and makes videos at crisis moments: when the color of his skin feels more curse than blessing; when his life purpose becomes unclear; when a loved one dies. Through his art, meaning rises, and lightness follows. “These pieces are like journal entries,” he says. “In each of them I seek to accept parts of my story—to find grace.” —Peter Bruun

ICanvas “Going to an elite boarding school had me thinking about the color of my skin as I never had before. Not being like everyone else—it being noticeable—there were times when I wanted to hide my brown skin. I lost myself paying attention to someone else’s story. In making ICanvas, I returned myself to myself. I am saying, ‘Here I am and look at me now.’ Look at me. I want you to look at me.” —Alexy Santos

ICanvas, 2019, Alexy Santos, 1:15 single-channel video, Voiceover: Alexy Santos

ICanvas, 2019, Alexy Santos, 1:15 single-channel video, Voiceover: Alexy Santos

A Life Well Lived “After graduating college, I didn’t know what was next. I looked around and saw all my friends in their careers; I saw my family with their jobs—some of my cousins had already started their families at my age. I wondered how to navigate my life; I wondered how to be a man within the context of Latin culture. Making A Life Well Lived helped me see no one can define your purpose—it’s a personal journey that depends on you specifically. Finding meaning? It’s a process. It’s like the journey I took within writing this piece.” —Alexy Santos

A Life Well Lived, 2019, Alexy Santos, 2:13 single-channel video, Voiceover: Alexy Santos

A Life Well Lived, 2019, Alexy Santos, 2:13 single-channel video, Voiceover: Alexy Santos

Bendicion Tío “In creating this piece, I thought about God’s grace—His blessing us not because of anything we’ve done but just because He wants to give it to us. With the love my uncle gave me, I didn’t have to do anything. That’s why it hurts that he’s gone. The more it hurts, the more I know I was loved, and the more I feel his grace. Making this piece, going into my uncle’s shoes—retracing his walks from when he was homeless—I could feel his love and that grace. I now feel him with me all the time.” —Alexy Santos

Bendicion Tío, 2020, Alexy Santos, 1:49 single-channel video, Voiceover: Alexy Santos

Bendicion Tío, 2020, Alexy Santos, 1:49 single-channel video, Voiceover: Alexy Santos

“And if by grace, then it cannot be based on works; if it were, grace would no longer be grace.”

—Romans 11:6

Photo courtesy Artist Estate Studio, LLC

HERMINE FORD

For decades, painter Hermine Ford has pursued an art practice steeped in grace.

As a painter, Hermine Ford’s practice is guided by a belief in continuity beneath rhythms of change. Whether inspired by the shifting sand dunes of Provincetown or the fractured mosaics of Ancient Rome, her art is all about what is now and always—past and present co-mingling, grace abiding. —Peter Bruun

“All we are, all we see, is nature…”

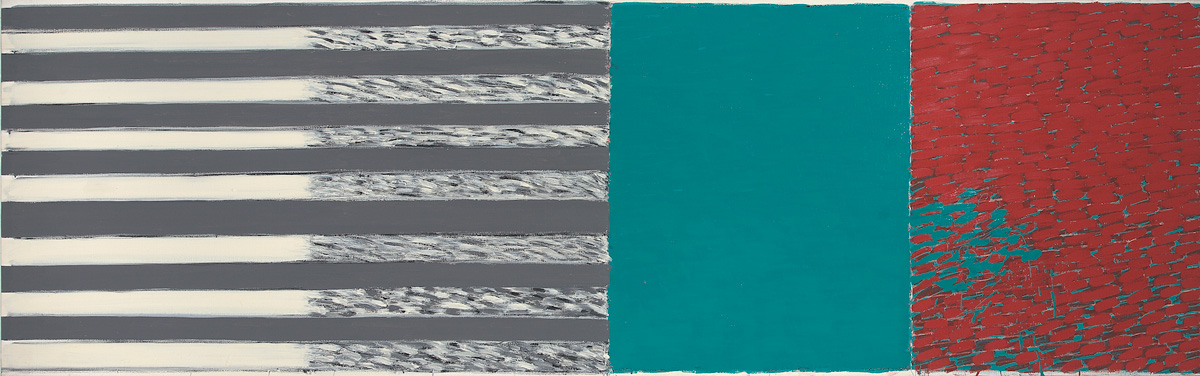

Untitled (246-75), Hermine Ford, 1975, 32.5” x 104.5”, oil on canvas

“Things grow. Or are made. Maybe by a human being, maybe by a bird or a bee. We make objects of all sizes, buildings, art. Then they get old, sometimes are torn down, even made to disappear, by water, wind, volcanoes, earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, or fire…” Untitled (220-09)

Hermine Ford

2009, 75.5” x 46.5” x 0.75″, oil paint, ink, watercolor, gouache, pencil and colored pencil on canvas on shaped wood panel

Untitled (220-09)

Hermine Ford

2009, 75.5” x 46.5” x 0.75″, oil paint, ink, watercolor, gouache, pencil and colored pencil on canvas on shaped wood panel

“Or they fall down from their own weight, or are pushed over, stepped on, shot at, blown up, smashed. Yet, the pure material remains…” Untitled (369-17)

Hermine Ford

2017, 22” x 30”, ink, watercolor, gouache, pencil, and colored pencil on paper

Untitled (369-17)

Hermine Ford

2017, 22” x 30”, ink, watercolor, gouache, pencil, and colored pencil on paper

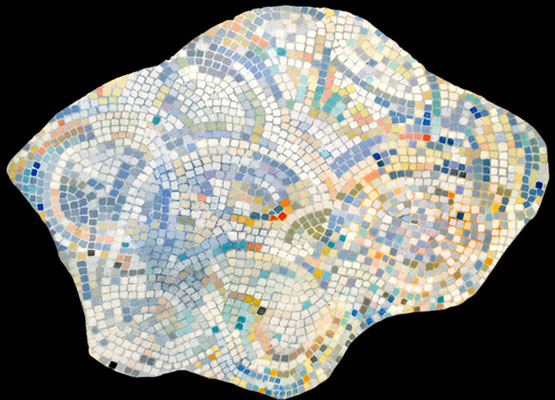

“The materials are reused down through the ages. Architecture and painting and sculpture are made from these raw and recycled materials…” La Nuvoletta

Hermine Ford

2013, 17.25“x 23.75” x 0.75”, oil paint on cotton muslin on shaped panel

La Nuvoletta

Hermine Ford

2013, 17.25“x 23.75” x 0.75”, oil paint on cotton muslin on shaped panel

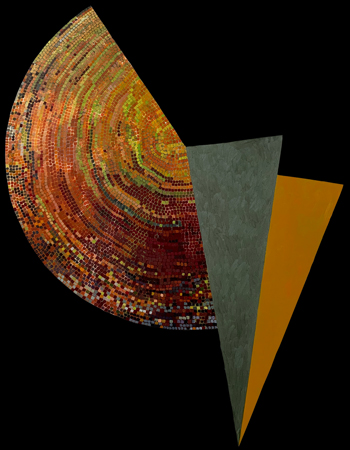

“An artist’s eye and hand moves over the materials while at the beach, or visiting an Italian city, or in the studio, remembers them as they used to be and rearranges them: the broken buildings, the stones, the tiles, the pigments…” Green Flash (400-2020)

Hermine Ford

2020, 54” x 41.5” x 0.75”, oil paint, graphite, colored pencil on muslin on shaped wood panel

Green Flash (400-2020)

Hermine Ford

2020, 54” x 41.5” x 0.75”, oil paint, graphite, colored pencil on muslin on shaped wood panel

“In my work I’m re-imagining the past, making it present.” —Hermine Ford

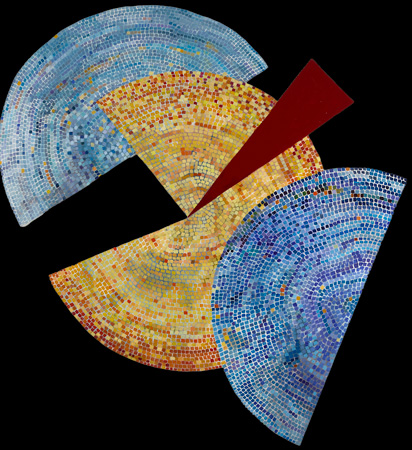

Spring Forward (414-2021)

Hermine Ford

2021, 47” x 45” x 0.75”, oil paint, graphite, colored pencil on muslin on shaped wood panel

Spring Forward (414-2021)

Hermine Ford

2021, 47” x 45” x 0.75”, oil paint, graphite, colored pencil on muslin on shaped wood panel

“The need to work at least a few hours several days a week is so powerful that I have asked myself why. The answer I’ve come up with is that it’s the one thing that integrates my whole self, where the self disappears, and becomes almost like a prayer. Is this ‘grace’? Perhaps.” —Hermine Ford

Public Programs

Speaking of Grace I:

Phylicia Ghee, Alexy Santos, Daniel Anastasio

In this FREE online event moderated by Peter Bruun, three young artists with work featured in Grace share their art and how it reliably delivers grace, bringing healing and largeness to their lives.

Thursday, July 15, 2021 7:00 PM ET

Speaking of Grace II:

Hermine Ford, circe dunnell, Alonzo LaMont

Three veteran artists who know something about challenge, loss, and redemptive grace. Join them as they share their wisdom and art in a FREE online conversation, moderated by Peter Bruun.

Sunday, September 26, 2021 7:00 PM ET

About the participants

Daniel Anastasio

Daniel Anastasio is a soloist, chamber musician, educator, and curator based in San Antonio, Texas. Having recently joined the faculty of San Antonio College, Anastasio is a member of Agarita, a San Antonio-based chamber ensemble dedicated to making classical music accessible to all, including the most under-resourced populations. He is also a member of Unheard-of//Ensemble, a Manhattan-based ensemble that champions new music and includes multi-media performances when on tour.

Alonzo LaMont

Alonzo LaMont is a Baltimore-based playwright whose writing has received national acclaim, including “Exposed to Strangers” receiving third place at the 2021 Tennessee Williams New Orleans Literary Festival. He has had original works produced in major cities throughout the United States (New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, Washington DC, and more), and overseas in Amsterdam, Holland.

Phylicia Ghee

Phylicia Ghee is an interdisciplinary visual artist and photographer whose artwork documents transition, explores healing, ritual, ceremony & personal rites of passage. Phylicia is interested in the intersection between the physical and the spiritual. Taught by her grandfather at a very early age, Phylicia works in photography, performance, video, fibers, mixed media, installation & painting. She earned her BFA in Photography with a Concentration in Curatorial Studies from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2010.

circe dunnell

circe dunnell is a mixed media artist who works in digital photography, ephemera and encaustic (molten pigmented wax). She has exhibited in New England, the Tri-State area and Graz, Austria. She has been a member of Studio Montclair, a New Jersey-based professional visual arts organization, since 1996, and teaches art at Rutgers Preparatory School.

Alexy Santos

Alexy Santos was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, home to the state’s largest concentration of Dominican-Americans, including his family. He graduated from Northeastern University in 2018 as a Marketing & Entrepreneurship major and currently works for IBM. Self-taught as an artist, Alexy uses writing and video-making as an outlet for personal expression, helping him make sense of who he is and who he aspires to be.

Hermine Ford

Hermine Ford has been working as a painter for more than 50 years. In that time, her art has been exhibited around the world, collected by major museums, and the subject of multiple publications and reviews. Hermine has been a visiting artist at major educational institutions, including the Rhode Island School of Design and Maryland Institute College of Art, where she also served as Resident Artist from 1986 to 2010.

Kathy O’Dell

Kathy O’Dell is an art historian and art critic whose articles and reviews have appeared in a variety of publications, including Art in America and Artforum. She is Associate Professor of Art History and Museum Studies and the Special Assistant to the Dean for Education & Arts Partnerships at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, where she has worked as a professor since 1992.

Peter Bruun

Peter Bruun is an artist, curator, and writer. He received a BA in Art History from Williams College in 1985 and went on to receive an MFA in 1989 from the Maryland Institute College of Art’s Mount Royal School of Art. Peter pursued his art practice in Maryland until 2019 when he moved to Maine, where he now manages all Bruun Studios activities.

Credits

Grace is curated by Peter Bruun, with website design by Megan McCarthy and development by Christie Wood. All photographs of Peter’s art by Dan Meyers. Special thanks to Daniel Anastasio, circe dunnell, Hermine Ford, Phylicia Ghee, Alonzo LaMont, and Alexy Santos for their generous participation in the exhibition, to Kathy O’Dell for writing the introduction to Peter’s art, and to Leigh Perkins for editorial expertise informing every aspect of the project. Grace is generously sponsored by the Nancy Patz Reading Fund.